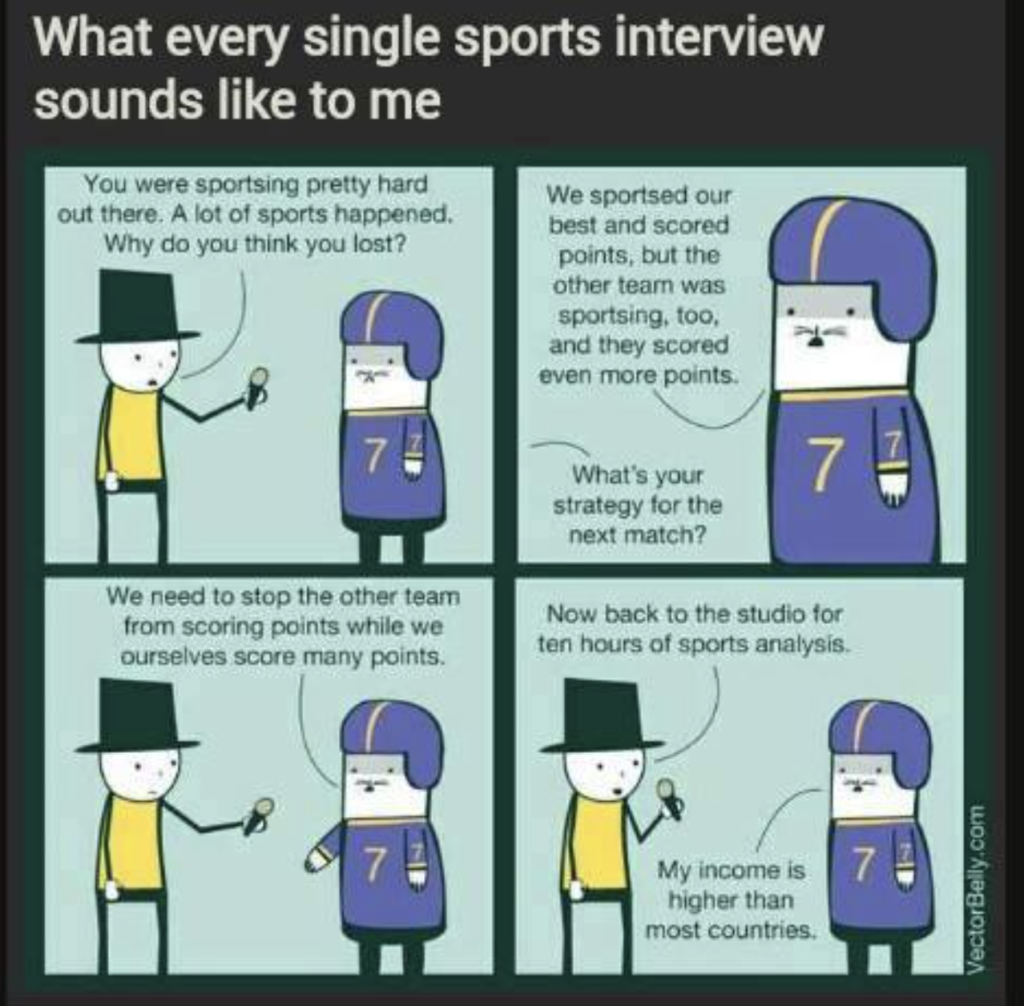

If you’re looking for one of the most important rules of sports journalism, it’s that you cannot be a fan.

It’s why after being a sportswriter from 1978 through the first part of 1996, it was probably 15 years before I could really cheer — even inwardly — for the teams I grew up following.

It isn’t that I stopped caring. In January 1988, when I was working as sports editor of the Greeley (Col.) Tribune, the two football teams I cared about most were meeting in the Super Bowl. Our paper covered the Denver Broncos, and I was certainly happy when they won games, but I had been a fan of the Washington Redskins since I was 13 years old in 1963.

I was invited to several Super Bowl parties, but I didn’t trust my reactions and I stayed home alone in my apartment and watched the game. After Washington went to its last Super Bowl in January 1992, the team went downhill and became an embarrassment under owner Daniel Snyder. It has been a very long time since I cared what happened to them.

I never had trouble with the “No cheering in the press box” rule, and I remember my friend Bill Madden being surprised in April 1985 when he and I were watching a hockey playoff game in a sports bar. No matter what happened in the game, I didn’t react.

It helped that it was rare to find myself in the press box covering teams that really mattered to me.

And on the rare occasions I saw real unprofessionalism on the part of others, it was mostly humorous.

One of the best stories I heard happened when I wasn’t there. I was covering the NBA Denver Nuggets in the 1987-88 season, and one of my reporters asked me if he could do the game with the Boston Celtics instead of me.

He told me the next day about a kid — I never knew his name — who was sports editor of his little hometown paper in Sterling, Colo. He was ostensibly interviewing Larry Bird after the game, but all his questions were about how disappointed he was that Julius Erving was retiring, and he asked Bird if he could talk him out of it.

Then came the topper.

“Larry, I love Dr. J,” he said. “Do you love Dr. J?”

Bird was highly annoyed, but he still reacted professionally. Then the kid lost it completely.

“Larry, can I have your autograph?”

The same kid had an even more bizarre moment the next fall at a Denver football game. On one play, wideout Vance Johnson broke free 15-20 yards behind any defenders. Quarterback John Elway didn’t seem to see him at first, and the kid from Sterling jumped up from his seat and yelled, “Throw the damn ball!”

Elway did, and the Broncos scored a touchdown.

The kid from Sterling was admonished for cheering in the press box.

The other best example is one I hardly remember. I was covering the Los Angeles Rams in 1991 or ’92, and one of the other reporters in the press box was a hulking guy who worked for a radio station in Bakersfield.

Radio guys were pretty much the worst. Newspaper people tend to look down on their broadcast counterparts for being shallow, and radio people more than television reporters.

I never knew this guy’s name either, but the Rams PR guy just called him “Bakersfield radio.”

At one point in one game, he made the mistake of cheering something good the Rams did, and the PR guy got on the PA system and said loudly, “No cheering in the press box, Bakersfield radio.”

Most of us just laughed.

I stopped being a sportswriter in early 1996, and while there are certainly teams I care about — mainly the Washington Nationals and the University of Virginia — my fandom for those two entities is something I keep pretty much to myself.

I’d hate to be lumped with the kid from Sterling and Bakersfield radio.