Editor’s note: This was originally published 15 years ago and has appeared several times in various forms. It will be included later this year in “Humor and Heart,” an anthology of my 40-plus years as a columnist in various venues. I thought this was particularly appropriate for Memorial Day.

Georgeanne Fletcher says Jon Rumble was never her friend in high school.

“I didn’t know who his friends were, where he lived or anything about his family,” she said. “We never shared a class or had lunch together.”

But thanks to a request from the drama teacher, Joan Bedinger, Georgeanne got to know Jon in the spring of 1967, and more than 40 years later, she still remembers him.

“Jon had been picked for the male lead in the senior class play, ‘The Unsinkable Molly Brown,’” she said. “Miss Bedinger asked me to help him learn his music. He had a good voice, but he didn’t read music and had been selected for his dramatic rather than his musical ability.”

So the two met, the serious piano player and the flamboyant young actor. At first, Georgeanne said, Rumble was quite irritating. He wanted to interpret the songs his own way, while she forced him to sing them the way they had been written.

“He wanted to direct the rehearsals, but I was having none of that,” she said. “He would stare out the window as if awaiting an admiring audience. When he saw someone he knew, he would race out in the middle of a phrase as if to impress upon me how much he was in demand.”

Eventually, it all started working. After Jon had his first rehearsals with female lead Penny Viglione, he came to appreciate what he didn’t know. Georgeanne said she learned to use his ego to her advantage.

“I started to praise his efforts, to encourage him to breathe deeper and produce a bigger sound,” she said. “Gradually his gruff manner melted and he turned a bit of his charm on me. He even startled me by calling me by my name and acknowledging my existence as a person.

“I was wary but he persisted and I actually regretted when the rehearsals ended.”

She remembers him as being so full of life. She asked her parents if they remembered Jon, and her mother said he reminded her of Paul Bunyan.

“He was a charmer,” Georgeanne said. “And with the lead in the senior musical, he was Master of the Universe.”

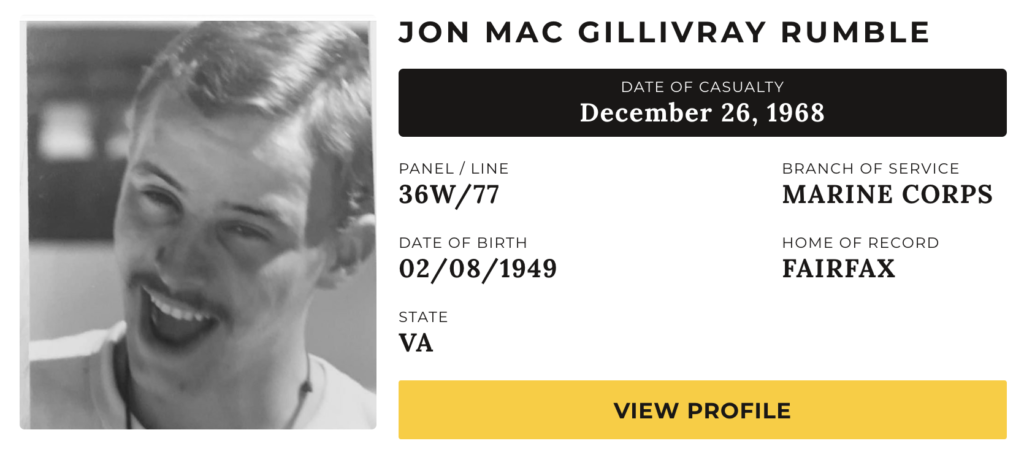

He was a master, but for such a short time. When he took his curtain calls that spring, Jon Mac Gillivray Rumble had less than two years to live.

***

There are no complete records of how many members of the Woodson Class of 1967 went to Vietnam. Some, like Mike Scott and Mike Willis, served and returned at the end of their tours to go on with their lives.

Another classmate, Mike Beale, was drafted and was scheduled to go to Vietnam but died at age 18 in a training accident before he ever left the country.

Jon Rumble was one of two who went and never made it back.

Along with Mike Sullivan and Beale, Jon died before he was even old enough to vote. And as the rest of us grew older, raised children and had careers, the three of them live in our memories only as we knew them in high school.

Forever young.

Jon Rumble was nearly at the end of his tour when he was killed on December 26, 1968, by small arms fire in Quang Nam.

He was one of the final casualties of 1968, the bloodiest year of the war, when 14,584 Americans died in a 12-month period that began with the Tet Offensive.

If there’s an irony in his death, it’s for all the people who fought so hard to avoid having to go to Vietnam, Jon wasn’t even supposed to be there. In fact, he had to sign a waiver in order to be assigned there.

“Two members of the same family were not allowed to serve in country at the same time,” said Don Dark, Jon’s best friend in the Marine Corps and a ’67 graduate himself from Portales High in New Mexico. “I gave Jon hell about that, as I know his brother did.”

Jon’s older brother Jed was already serving in Saigon in the Army 101st Airborne Division, so there was no way he would have been sent there unless he insisted.

“There was no swaying his opinion,” Dark said. “He felt that he was there for a reason. I used every angle I could think of, including mentioning the fact we were being used as cannon fodder and patsies, but he was firm in his belief. I came to admire him for that very much. Jon was a warrior and a person of high principles.

“I became a better human being because of him.”

***

It’s funny how many lives Jon touched, even in the short time he lived. Joe Perszyk, whose family lived near the Rumbles in Mosby Woods, said Jon quickly became his best friend after his family moved from California to Virginia in the summer of ’66.

“I attribute a number of good things in my life to Jon,” Perszyk said. “He brought me out of a shell I had been in and made me look at the world and life in a whole new manner.”

Just as Georgeanne Fletcher remembers him working hard to get what he wanted, Perszyk recalls how focused his friend could become when he set his mind on achieving a goal.

“Jon used the same motivation that won him the leading role in the class play to prepare himself for the U.S. Marines,” he said. “He wanted so much to be in top shape before he went to boot camp and he worked out incessantly every day. Using free weights, doing sit-ups and push-ups and running, he was determined to be in better shape than any other recruit in his basic training group.”

He came from a military family. His father was a naval aviator, his uncle

had been an admiral and his older brother Jed was in the Army. Jon joined the Marines in the late summer of 1967 and came home for Christmas that year.

“It was the last time any of us saw him alive,” Perszyk said.

Jon had only been in Vietnam a short time when he volunteered for the Combined Action Program, an experimental unit designed to live and fight with local militias in villages throughout the northern areas of South Vietnam.

“The experiment was as brilliant as it was asinine,” Dark said. “The theory was that if you placed small units of seasoned combat Marines in or near hostile villages, through integration you would eventually win the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people. It was sort of like a highly armed Peace Corps with an attitude.

“First and foremost, we were to eliminate the Viet Cong living in said villages. Next we were to keep the VC from raiding the villages of rice, money and more importantly of new and forced volunteers. We were also to train the local militia, provide medical attention, and encourage a lifestyle of peace and harmony. In other words we were to create a utopian society in a foreign country that wouldn’t work in Bakersfield, California.”

There was one basic problem with the concept. Anyone who met the requirements of Vietnam combat duty was already jaded in his perception of the Vietnamese people, both the civilian and military. Who were the friends, who were the enemies?

“Trained to hate the enemy in a country where friend and foe were indistinguishable, the easy choice was to hate them all,” Dark said. “CAP Marines carried this baggage with them to their new assignment.”

But despite that, they did a remarkable job. Woodson classmate Mike Scott points out that they enjoyed a perfect record of never allowing a village to fall back into enemy hands. Eighty percent of the CAP Marines were wounded, 50 percent more than once. One in five of them were killed, but even so, the CAP had the highest percentage of people volunteering to return to their units in all of Vietnam.

“It was a very small and personal fight for them,” Scott said. “Jon spent his nights making sure the local Viet Cong political officer didn’t come to take the teenage sons and daughters away to be inducted in the local platoon.”

Rumble sat for hours every night in an ambush site, refusing to sleep until he was certain nothing would happen. He averaged about four hours sleep and then spent his days working with the people of the village, helping with their rice harvest and helping them build schools.

“One fact that the news never covered even once,” Scott said. “When a CAP Marine was killed in the village he was defending, the tears rolled down the faces of the villagers too. As we do, they will always hold those Marines in their hearts.”

***

Don Dark, who lives all these years later in Dana Point, California, has no doubt that if Jon had survived the war, the two of them would have been close friends for life.

“It is hard to describe how strong the bond that develops between people who have been in war together is,” Dark said. “In the environment of war even people that you wouldn’t give the time of day to during normal circumstances ends up being tighter than any friend that you had prior to that. So imagine how close you would be to a person that under any circumstance you would consider him to be a best friend. That was the nature of the friendship that Jon and I had.”

They patrolled together, they hung out together and they got high together while talking about how ridiculous the war was.

“We were hippies with an M-16 who shared a similar background,” Dark said. “We were both military brats and as such we were destined to be where we were. We joined the Marine Corps with the belief that it was our responsibility to do so even though we had misgivings.

“By the time we met, we both had the same view of the war. We knew that all the lives lost were in vain that, given the politics of the time, we were not there to win a war.”

Just before Christmas 1968, Dark was offered the opportunity to take some time off for R&R – rest and recreation. He had been in Vietnam for 11 months and he was given a week out of the field to have some fun in Sydney, Australia.

He almost hadn’t gone. He said that by that point, both he and Jon were short-timers and they were looking out for each other. He had less than three months left in his tour, and Jon was also down to fewer than 100 days.

“On my way back to the unit, I remembered Jon’s brother Jed was coming up to visit him for Christmas,” Dark said. “It was December 23rd, and by the time I got back, I was in pretty good spirits. I knew Jon would be jazzed to see his brother and I was happy I would be there to meet him.”

Only he wasn’t. He never saw his friend again. Jon had been transferred from Namo, a village north of Da Nang, down closer to the giant U.S. air base in Da Nang, a move Dark later learned was intended to keep him safe for his final month in country.

He found out later that Jon and Jed’s father, Captain Rumble, was being transferred to Vietnam in January 1969 and that both of his sons would be leaving the country.

“I learned many years later that Jed had come to Da Nang to tell him that and that he wanted to make sure Jon didn’t resist,” Dark said.

The very next day, Jon was killed by sniper fire in Quang Nam.

“The first thought that came to my mind was, ‘Jesus, it’s Christmas in the states, his poor mother,’” Dark said. “The next was to find out if Jed was OK and we were assured he was. I was numb for the next several hours. The truth is, I was numb for the next 38 years.”

The following day, the company’s gunnery sergeant came out to the field to see Dark. He had the wooden box in which Jon kept his personal belongings, and he said Jon had requested that it be given to Dark if something were to happen to him.

That was the point at which it really sunk in that Rumble was gone. Dark looked through the box and found mostly letters from family, friends and a girlfriend, as well as a pipe the two men had carved out of wood.

“That night I held my own funeral service for Jon,” Dark said. “I burned the box and its contents and smoked some weed with the pipe and then threw the pipe into the fire.”

He burned the box because he figured Jon wanted to insure that the letters were not sent home to his parents with the rest of his belongings. Dark decided that if something happened to him, someone going through his belongings might find Jon’s letters and his parents might still get them.

He didn’t want to take that chance.

Joe Perszyk remembers that time from a different perspective. It was December 27th when Jon’s mother called him and asked him to come over to their house. His first thought was that one of the boys, either Jon or Jed, must have been wounded.

It’s funny sometimes how our minds reject the possibility that the worst might have happened.

“When I walked into the house through the side door that led into the kitchen, Jon’s mother was in tears,” Perszyk said. “She told me Jon had been killed. The whole world stopped for me and I was hoping it was a big mistake.”

Jed had been sent home immediately, and Perszyk went with Rumble’s parents the next day to pick up their surviving son at Dulles Airport. When Jed got into the car, he told them something they hadn’t known at that point.

He had been with Jon when he was killed.

Jed Rumble had been on leave from the 101st Airborne when a firefight broke out near where he and Jon were located. They went with a couple of Vietnamese to check it out. When they came to a hut, Jed went inside while Jon went around the back to see if there was anyone there.

“After a short period of time, one of the Vietnamese men came into the hut and told Jed that the Marine had been shot,” Perszyk said. “A sniper had shot Jon in the head, through his helmet. He was dead when his brother got to him.”

He was 19 years old.

“I don’t remember when I first heard that he had been killed,” Georgeanne Fletcher said. “I had been skeptical of the war from the beginning and I wondered what he was doing over there. Did he think that war would be another great adventure? Another stage to perform on? I had been irritated with Jon in high school and I felt furious with him because he died.”

Perszyk says that isn’t the case, that Vietnam had been anything but a great adventure for his friend. Rumble had been enthusiastic when he enlisted, but in his letters it was apparent that the enthusiasm had faded badly and he was very much in doubt about what it all meant.

In fact, Joe Perszyk still has a picture of his friend, sitting cross-legged on the ground with his right hand in the air.

“He was forming a peace sign with his fingers,” he said.

***

It says a lot for Jon Rumble’s personal magnetism that people – both close friends and some who barely knew him – still think of him 40 years later.

The first time Georgeanne visited the Wall in Washington, D.C., she found his name and touched the letters.

Then she cried.

“Not the usual silent tears,” she said. “I sobbed. I think of Jon when I listen to the music of the Doors. He’s the image in “The End,” he’s the “actor all alone” in “Riders on the Storm.” I thought of him in “Les Miserables,” the young man killed in the revolution. ‘There are storms we cannot weather.’”

Joe Perszyk couldn’t even bring himself to visit the Wall and look for Rumble’s name until 2002.

He hasn’t been back.

“There was a group of us who hung out together that included Jon,” he said. “We remain friends to this day. The memories are still very real and the pain of Jon’s death comes back from time to time.”

Mike Scott says he believed Jon loved what he was doing and that his death meant something.

“Most of us will die quietly in our beds,” he said. “He died upstaging us all.”

***

A few years ago, Don Dark got an e-mail from Maggie Rumble, Jon’s younger sister. He still isn’t sure how she found him, but the letter started a correspondence between the two of them that resulted in a meeting between Dark and the Rumbles over the Thanksgiving 2006 holiday in Las Vegas.

“As the day drew closer, I became more and more apprehensive to the point that I wasn’t sure if I could pull it off,” Dark said. “I don’t know why I reacted the way I did, I guess that the guilt I felt for so many years was coming full circle and in some ways that guilt was comforting and familiar and defined my war.”

They had dinner together at the Flamingo — Don, his wife and son, and Maggie, her mother and brother Jed, his wife and son, were there. Captain Rumble had died in a plane crash not long after Jon’s death.

“With tears running down my cheeks I raised my glass for a toast to Jon and unsurprisingly, everyone at the table had the same reaction,” Dark said.

After the dinner, Dark and Jed Rumble had a private conversation.

“Although we hadn’t met before that evening, Jed was Jon’s older brother, and since I thought of Jon as my brother, that made his brother my older brother,” Dark said. “I immediately blurted out my sense of guilt about not being there to protect him. Jed told me that there was nothing that I could have done to change the inevitable.”

Jed told Dark that his brother had told him on Christmas day that he was not going to make it home. It wasn’t the first time Dark had heard this; he and Jon discussed the same thing many times.

“I guess I didn’t take it seriously because countless times I had said the same thing and at the time truly believed it,” Dark said. “Jed told me with sincerity that I could read in his eyes, so I believe it to have been something that Jon knew all along.”

He still misses him, more than 40 years later.

“Jon was a great person,” he said. “The world is not a better place without him.”

***

In the end, Jon Rumble was a showman, and the last memory of him that most of the Class of ’67 has is a good one. Georgeanne Fletcher, now Georgeanne Honeycutt, still remembers the last time she saw him, on the stage picking up his diploma on June 5, 1967.

“Jon’s antics at graduation are one of the most vivid of my memories of that event,” she said. “He had boasted and made a big deal that he might not graduate. When he received his diploma, I was seated and had a full view of him as he crossed the stage. He made a grand gesture of relief.

“A few weeks earlier, it might have irrTom Kensler and I were good friends for itated me, but I joined the laughter and applause as he exited.”

Exit – stage right. Forever young.