I have mentioned before that after my 40th high school reunion in 2007, I started a project looking at the Class of 1967 approaching old age. I actually wrote a dozen or so chapters, but then I hit a point in my life where there was great turmoil, both career-wise and health-wise.

The book never got written, and in fact at least one ore two of the people I wrote about is no longer alive. As the Class of ’67 heads into its mid 70s, I realize some of the stories are worth telling and retelling. Two of the ones I have already shared here are ones that still bring tears to my eyes — Jon Rumble who died in Vietnam and Tony Barile who was part of the story of one of Americaq’s greatest sports tragedies.

Another story that truly amazes me — the subject, not the writing — is a classmate and friend who survived the greatest plague of our lifetime and in fact has lived with it for 40 years. I know of two people living long-term with HIV and maintaining their health. One is Magic Johnson, the other is my friend Dudley Wilson.

This story was written in 2009, and I will include a present-day update at the end.

***

I WILL SURVIVE

Many of his friends are dead and gone, but Dudley Wilson lives on the far side of America with a sense of love and peace.

Dudley Wilson doesn’t worry about anything these days. When he watches the sunset each night from his house on Kauai in the Hawaiian Islands, he knows that life is good.

And besides, he’s been playing with what gamblers call “house money” for a very long time.

Dudley has been living with the human immunodeficiency virus – the plague of our generation known to most as HIV – since at least 1983 and possibly longer. He knows that each day and the one that follows are a gift beyond measure, and he has been making the most of the days he has been given.

“I don’t take any day for granted,” he says.

***

Dudley Wilson knew he was gay as early as junior high school, but he kept it to himself. In those days long before Stonewall and gay liberation, there wasn’t much to celebrate or be happy about.

“I remember seeing a film about a homosexual predator and worrying that would be me,” he said. “The film told us that if you were homosexual, that is what you would become. I was quite tormented by the thought and wanted so badly to be ‘normal.’”

Life was difficult enough without that burden. Between his sophomore and junior years of high school, Dudley’s family moved from Hawaii to northern Virginia. He went from an extremely laid-back culture to one that was anything but. Into a culture that was all about the preppy, collegiate look, he brought his own style of Hawaiian shirts and green tennis shoes.

“The first year people didn’t know what to think of me,” he said. “By the second year I think I was part of the somewhat diverse scenery.”

He didn’t consider himself part of any one group, throwing himself into drama, chorus and student government. He was popular enough in the groups he was involved with to be elected president of the Drama Club and was active in most of the productions during his two years at Woodson.

But he was still fighting with himself about who he was.

“I had male sexual experiences when I was in high school,” Dudley said. “After which there was always shame and regret.”

He wanted to be “normal.”

***

Of course “normal” in those days was fairly rigidly circumscribed. Any of us who rejected our parents’ model of how to live – a spouse, a house, some kids and the elusive white picket fence – were in for a lot of anguish.

Actually, Dudley went that route. He spent four years at Rollins College in Florida and graduated in 1971. Two years later he was married and teaching at Fairfax High.

“I felt like I was swimming against the current,” he said. “I made life very difficult for myself. I hadn’t yet learned that you can’t change people’s opinions.”

But times were changing. In June of 1969, the New York City police raided a popular club in the city known as the Stonewall Inn. The patrons resisted, and the ensuing riots wound up being the event that galvanized the gay community.

A month after the riots, on July 31, the Gay Liberation Front was formed, and the name of its magazine — “Come Out!” — was an indication of its politics. By the end of 1969, there were more than a dozen gay activist groups in the U.S.

That might not have meant much to a kid starting his junior year at a small college in Florida, but as the ‘70s wore on, the gay scene became less and less closeted and particularly in cities like New York, quite open.

In 1979, Dudley left his wife, rented out the house he owned and moved to Dupont Circle. He quit his second master’s degree program at Catholic University, left his job as a teacher and enrolled in hair dressing school.

If that sounds a little bit like a cliché, it’s important to remember that there was still a great deal of job discrimination against gay people in those days. Even if he had wanted to continue teaching, it probably wasn’t an option.

***

Dudley was 30 years old in the last summer of the 1970s, but in terms of being an openly gay man, he was much younger. He found he had to go back and experience a lot of things he hadn’t done in his 20s.

“I got married when I was 23,” he said. “I was so serious all through my 20s. So at 30, I embarked on my ‘gay adolescence.’ I was like a kid in a candy store. All I wanted to do in my early 30s was to go to school and then party at night.”

The late ‘70s and early ‘80s might be called the heyday of the gay culture. People were out and proud, celebrating their sexuality and enjoying life to the fullest. Just as kids tend to think of themselves as bulletproof or invincible, no one could imagine the pandemic just over the horizon.

The first cases of what would turn out to be Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome were reported in June 1981, when the Centers for Disease Control recorded a cluster of a certain kind of pneumonia in five gay men in Los Angeles.

No one really knew what it was, and before the name AIDS was coined, the CDC often referred to it by way of the diseases associated with it, such as lymphadenopathy. It was also called Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections. Since most of the victims at that point appeared to be gay men, the press called it GRID, for Gay-related immune deficiency.

At one point, the CDC called it “4H Disease,” since it seemed to single out Haitians, homosexuals, hemophiliacs and heroin users. Once it became apparent that the disease affected more than just homosexuals, GRID became misleading. In 1982, the CDC started using the name AIDS and properly defined the illness.

Scientists now believe that HIV and AIDS have been in the United States since the late ‘60s by a Haitian immigrant who contracted it while working in the Congo, but even in 1982, when the term made its public debut, it was still relatively rare. Few people knew it was passed by sexual contact, and not many people were looking at celibacy or monogamy as a way to avoid it.

“In the early ‘80s there was a lot of casual sex and drugs,” Dudley said. “Cocaine was everywhere and many of my friends did it on and off. Behind all of this for me was my desire to find Mr. Right.”

He was certainly looking. Wilson remembers weekends in the early ‘80s when he would finish work around 4 p.m. on Saturday, get on a train and go to New York. He met friends in the city, went out to dinner, went back to their place for a “disco nap” and then go out dancing.

“We went to the Saint, the old Fillmore East, and danced till 8 or 9 the next morning,” he said. “Then we went out to breakfast and then to the Limelight to dance for a few hours.”

By afternoon he was back on a train to Washington and his daily life. It must have seemed like living in Kansas and getting to visit Oz every weekend.

“I always loved dancing and this was still the Disco Age,” Dudley said. “I was out dancing as much as I could, of course looking for love, but what I found over the next couple of years was that you meet a lot of alcoholics in bars. Still, it was all very exciting.”

It was, but an era was ending and no one knew it at the time.

***

In 1983, Dudley met a man who he thought was the love of his life. They were together for three years, partying heavily and doing large amounts of cocaine and alcohol.

“I realized I wasn’t raised to live that kind of life,” he said. “I bailed with much sadness and confusion.”

Something else was happening that contributed to the sadness. By 1986, large numbers of gay men were becoming ill and dying of AIDS. Many of them were Dudley’s friends.

It was a terrifying time. Throughout his entire first term, President Ronald Reagan had never publicly mentioned AIDS, and many conservatives resisted increasing funding for research because they saw the disease as a sort of cosmic punishment for bad behavior.

Two patients started to change that. Film star Rock Hudson, who had been a closeted gay man for most of his life, announced in 1985 that he had AIDS. And Indiana teenager Ryan White, a hemophiliac, contracted the disease because of a blood transfusion. Hudson died that October, but White lived until 1990 and put a human face on AIDS for many Americans.

But in the gay community, every day became a sort of Russian Roulette.

“None of us knew if ‘the bug’ would hit us next,” Dudley said. “We were told not to have an HIV test once it was developed, because if we were diagnosed, our insurance companies would deny us further coverage.”

Besides, in 1986 there was no medication that could treat the infected. Gay men checked their bodies daily, looking for lesions, moles or bruises that wouldn’t go away.

“Any new mark was a constant worry,” Dudley said.

Not to mention the fact that he was losing friends. He didn’t want to know if he was infected, but when he realized how many of his former sexual partners had died, he knew his odds weren’t very good.

“I can remember leaving the salon one day,” he said. “I stood at the front door trying to decide which way to go. If I went to the left, I would go to one hospital to see a dying friend. If I went to the right, I would go to another hospital to see another dying friend.”

Both men died within weeks of each other, and the funerals began piling up. After a while, Dudley says, he couldn’t bear to go to funerals anymore.

“We had cocktail parties to celebrate our fallen friends,” he said. “We even made them ‘fabulous,’ spreading the ashes of one of our friends on the dance floor of the dance palace in Pines, Fire Island.”

If there was one benefit he gained from this period of his life, it was a deeper sense of spirituality. Dudley served as the facilitator for a mediation group for those who were infected that met weekly, and it was at that time that someone told him he could find out his status without actually taking an AIDS test.

They suggested having work done to check the status of his T-cells, white blood cells developed in the thymus – hence the name – to fight infection. Someone with a compromised immune system would have a lower T-cell count than normal.

It was an easy way to find out if one had “the bug,” so Dudley decided it was time to learn the truth.

Of course in his heart he already knew.

***

“I remember calling the doctor’s office after work one day to get the results,” he said. “The doctor had left for the day, but his associate looked in my file and told me that I was in the middle of the infection and would start exhibiting symptoms in a couple of years.”

It sounded like a death sentence.

Dudley said that he had not had the test and didn’t even know if he was infected, earning him an angry retort that he had not gone through the proper protocol. He went on to get the HIV test anonymously in May 1987 and learned that he was indeed infected.

More terror.

“I felt fine,” Dudley said. “All I had was lower T-cell numbers.”

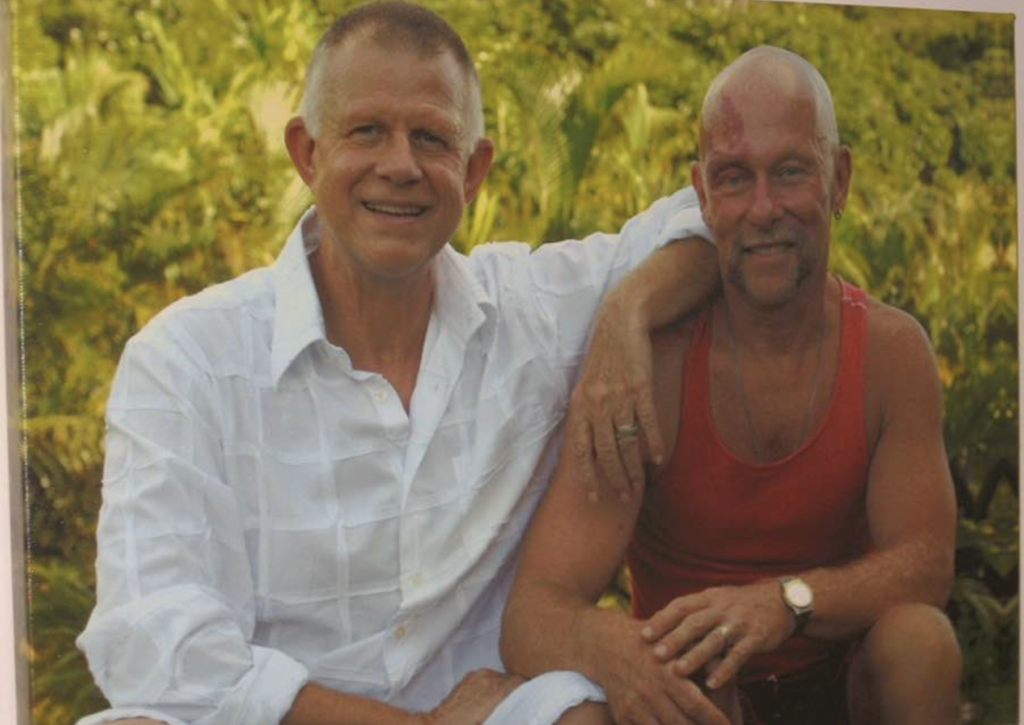

Ironically, all this happened four months after he had finally met his Mr. Right. James Jennings had been with his previous partner for 17 years before AIDS had taken him away in 1983.

Dudley says he didn’t know what to expect.

“James could have run in the opposite direction, but he has been my support and my friend,” he said. “He helped me navigate the medical maze to eventually get the treatment that has allowed me to survive.”

Jennings would never have run. He knew Dudley was someone special, someone worth knowing.

“Dudley was when I met him and remains one of the kindest humans I have known,” he said. “In a city like Washington, D.C., filled with pretense, Dudley has never had any and is just as decent to the homeless people he encountered on his walk to his salon as he was to the high and mighty in politics who sat in his chair.”

For the longest time, Dudley expected to die soon. Back then, nobody was living with HIV for more than 10 years or so before developing full-blown AIDS and dying, and as far as he knew, he could have been infected as early as 1979.

“I kept expecting the other shoe to drop,” he said. “I wasn’t even 40 and so many had died in their 30s. It all seemed surreal. Everyone seemed to be living their lives but didn’t seem to realize that it was all coming to an end.”

But something strange happened. Dudley did his best to live a healthy life, to stay positive and upbeat, and he didn’t develop any symptoms other than the lowered T-cell count. In the 1990s, when scientists first developed the drug “cocktail” that enabled those infected with HIV to maintain their status instead of further declining, he began taking it.

Jennings, who has spent much of his life working with those suffering from HIV/AIDS, says that it’s important to remember that one reason Dudley is alive and well – managing a chronic disease as opposed to dying of a long, drawn-out terminal illness – is because he has been uncommonly disciplined about his medication regimen and his checkups.

“He also has had outstanding specialist attention from Dr. Robert Redfield of the Institute of Human Virology in Baltimore,” James said. “I say this because data is very conclusive about the power of strict adherence to drug regimens as key to controlling viral replication and achieving stasis with the infection that leaves it in place but not active.

“Any sense that Dudley has just been a lucky guy does a disservice to those who should know that HIV disease does not have to be a death sentence but has to be taken as seriously as humanly possible to checkmate it. His attitude has played a very consequential role in his ability to remain healthy and fit all these years later.”

He’s still taking it just as seriously, and a young man who never thought he’d see age 64 all of a sudden began considering the possibility.

“I don’t know,” he said. “I’m just getting used to turning 60; I can’t get my head around 64 yet. I am very active – I go to the gym at least five days a week and exercise for an hour each time.”

He’s joining a men’s hula group, he’s surfing and he works in his garden. He plans to travel some, but he says the more time he spends on Kauai, the more difficult it is to leave.

“It doesn’t get any better than this,” Dudley said. “I don’t feel like the HIV poster boy even though I am living with HIV. The only time I think of the disease is when I take my pills every morning; the rest of my day and evenings are spent enjoying and appreciating the things most people do and worrying about the same things too.”

When he looks back at the long, strange trip the Class of ’67 and the baby boom generation have taken, the one thing that strikes him is how innocent we were, how idealistic and pure in so many ways.

“We were so different than the generations that came before us,” Dudley said. “We thought we were so special. As life would have it – and it always does – those visions slowly melted away and we had to decide where we belonged in this world and how we could feel comfortable in our own skin.

“In the end, it isn’t about how much money we have or what our job was or what we have done. It really is whether we like ourselves and are we at peace with the choices we have made, both good and bad.”

***

Dudley Wilson lived through one of the horror stories of our generation and came through it with the life he always wanted.

That isn’t to say that the memories don’t haunt him sometimes.

“I am not afraid of death,” he said. “I am only concerned about the process. I have spilled my guts telling this story and have relived some times that were horrific and resurrected many ghosts. I miss many of those men. In many ways I had to start over to make new friends.”

He stopped counting when the number of friends lost to AIDS reached 80. Not all were close friends, but all are memories of a time when they were young and strong and they thought the party would last forever.

Of course it rarely does. Something almost always steps in, whether it’s something as simple as responsibility or something as profound as death.

But once the party ends, if we’re lucky, there is real life.

“I have a loving partner and four dogs and live on the edge of a valley overlooking a river,” Dudley said. “HIV has been a gift to me in so many ways, not that I would wish it on anyone else. It has changed the way I live my life and the things I hold dear.”

If there’s one thing James knows about his partner, it’s that Dudley leads from the heart more than the head.

“His long march with HIV disease has given him a level of empathy for anyone facing a tough life situation that is comforting and endearing,” James said.

It’s the way he wants to live.

“I don’t take any day for granted,” Dudley said. “Today is the only day we have for sure and we must live it to the fullest.”

***

2023 update: When same-sex marriage became legal, Dudley and James were married. They were together until James passed away in 2016. Dudley moved back to Virginia and is still hanging in there at age 74. To steal a line from Gloria Gaynor, he has survived.