THE END

In the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.

I would never call myself an unselfish person.

It took me long enough even to be able to think of myself as a good man, to find a way to define myself as someone other than a person who still wanted to accomplish something.

But these days if you were to ask me to describe myself, to tell you what matters most to me, the answer would be easy. I am a family man, the grandfather of Madison and Lexington Kastner, the father of Pauline Kastner and Virgile Borderies and the man who loves Nicole Rappaport.

In fact, the woman I will love until my final breath and beyond is the person who taught me the true meaning of love, that sometimes love hurts so much you feel you can’t breathe, that sometimes it’s the only thing in the world that matters and most of all, that love is much more important to give than to receive.

If I had known that earlier, my life might have been very different.

***

Let me repeat that I would never call myself unselfish. It was always about what I wanted to accomplish, the world I wanted to gain for myself. I don’t know that I ever spent one day in my four years at Woodson satisfied with who I was or what I had. I was a perfect example of that old Groucho Marx saying about not wanting to belong to a club that would have someone like me as a member.

I was a smart kid who wanted desperately to be a jock, and when my 10th grade gym teacher, Fred Shepherd, saw me throwing perfect 50- and 60-yard spiral passes in class and said I should be playing football, it might have been a dream come true. But when I took the permission slip home and my parents refused to sign it, my heart was broken.

It didn’t matter to me that I was only 5-7 and 135 pounds. I was only 14, and I figured I’d grow. They figured I’d get killed, and they were a lot more willing to deal with my unhappiness. At least I’d know they cared.

I didn’t see it that way. We had moved to Virginia a year and a half earlier, when I was halfway through eighth grade. I had gone from the Dayton, Ohio, suburbs to a place where people actually cared on which side of the Mason-Dixon Line I had been born.

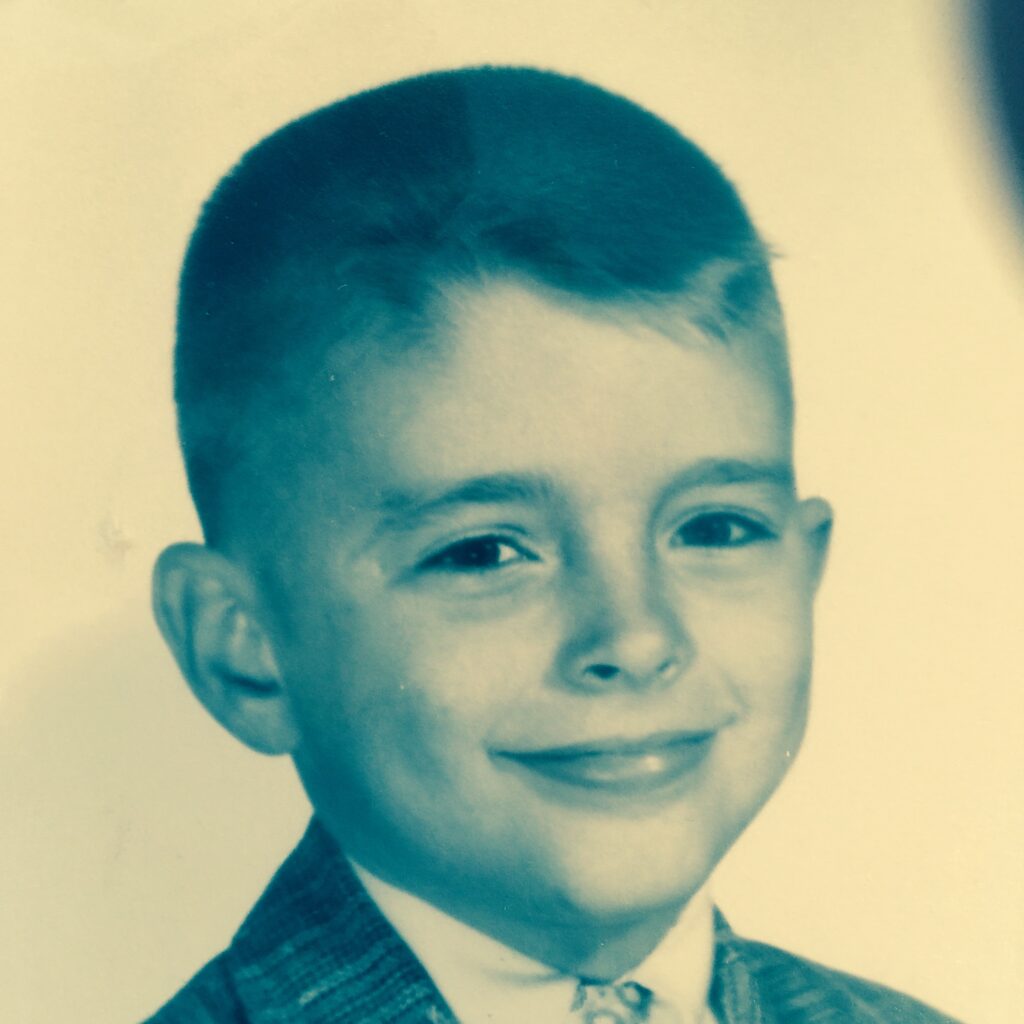

I didn’t make friends easily at that age. It didn’t help that I had skipped a grade in elementary school and was a year younger than most of the kids in my class. Being what Dave Barry called “puberty impaired” was hardly a plus, either; when I look at my ninth grade picture, I see a kid who looked like he was 10 years old.

I had three good friends in ninth grade – Gary Oleson from my own neighborhood and Tracy Antley and Alan Singer from English class. All three of them were bright kids who were comfortable in their own skins. Alan’s family moved away early in our Woodson years, and Tracy’s father was transferred down to Quantico before our senior year.

Gary was the only one who graduated with us, and he was everything I should have been. He got wonderful grades – I think he was fourth in our class – and went to Princeton. He didn’t try to be anything he wasn’t, and he was outstanding at everything he did. I don’t think I ever told him how much I admired him for that.

Tracy was the first girl I ever really wanted for a girlfriend, and of course it eventually got in the way of our friendship. Tracy Antley-Olander, now a Seattle attorney, remembers those days.

“I met Mike in ninth grade,” she said. “He, Alan and I quickly formed a bond. We were all outsiders in that sea of suburban teenagers. I was short and looked 11 years old.”

Tracy had just moved to Virginia from California. She was smart and knew it, in an age before intelligent young women were really appreciated. More girls wanted to be cheerleaders than honor students, and plenty of them were still going to college to find husbands.

“I recall one day some jerk in English class told me encyclopedias didn’t get taken out,” Tracy said. “Alan and Mike were smart, too, and they were not offended by a smart girl. It was my first realization about the kind of guys I wanted as my friends.”

Eventually she realized I wanted more and she started avoiding me. She didn’t know about the problems I was having, or my struggles with the kind of person I was. She just knew I wasn’t happy, and she thought it was her fault.

If there’s one thing about old friends, it’s that sometimes they remember things you had managed to suppress. Tracy recalls that one day in the spring of our junior year – I think it was right around the time I lost the election for Student Government president – we had our final showdown.

“Mike cornered me in the Earth Sciences room over lunch and told me his feelings,” she said. “He even sang a few lines of a song – ‘What Kind of Fool Am I.’ I fled.”

It must have been the singing. I’ve never been able to carry a tune, and the thought that there was a time in my life when I actually tried to sing my feelings to someone – in a show tune, nonetheless – makes me cringe. My only salvation is that even after having the moment described to me, I still don’t remember it.

***

People who didn’t know me as well didn’t run into such embarrassing moments. I managed to fool some of them into thinking I was well adjusted.

“I remember you as a clear-eyed, bright student,” Georgeanne Fletcher said. “You let your hair grow long in the front and I remember how you shook it when you had a point to make. You were also quite funny.”

Was I funny? I suppose so, but actually I was what Kris Kristofferson would one day call “a walking contradiction.” I don’t think I got an “A” for the year in a single class other than band or physical education in four years, although I was a National Merit Finalist and got nearly 1,400 on my SATs. In one of the few classes I enjoyed, American History, I got B’s on my report card all four quarters and then got a perfect score on the final exam.

“I hate you,” my teacher, Janet Martin, said with a smile on her face.

She was kidding, but there was probably some truth in her words. If there’s one thing I’ve seen over the years, it’s that teachers love kids who work hard and overachieve, and they aren’t all that fond of kids who don’t use their talents.

My problem was that I couldn’t allow myself to do well. I was at war with my parents, although it was a war only I was fighting. They wanted me to excel in school, so I did poorly. They wanted me to read great books and love great music, so I read trashy popular novels and listened to rock and roll. I was the king of passive-aggressive behavior.

It all sounds incredibly stupid to me now. When I look back on the wasteland of my teens and twenties, at flunking out of college three times and at a first marriage that was destined to fail before we even got engaged, I marvel at the fact that I could have been so self-destructive. It’s almost impossible for me to accept that the younger, crazier version of me stopped going to classes and skipped taking my exams in three different semesters at two different schools.

I don’t know when it was that I finally began to mature. I suppose if I were to divide my life to date into three parts, it would be somewhere near the end of the second third that I started feeling good about myself. I was working for a major newspaper covering college basketball and I was in the best shape of my life physically. When my employer went out of business, I landed a job as sports editor of a small daily newspaper in Greeley, Colorado, and for the first time in my adult life, I was living somewhere I really wanted to be.

All that was missing was somebody to love. I had been living alone for nearly eight years, and if there was one thing I still wanted in my life, it was a wife and children.

I think I was 34 the first time I dated a woman who had children. It was the first time I started to realize that maybe the quickest way to a family might not involve my DNA, and that I might not have to go through nine months of “we’re pregnant” and then a couple of years of raising an infant.

After what I had been through, I wasn’t sure that my genes should be passed along anyway. And if I couldn’t pick the father, maybe I could at least pick the mother.

There were some interesting ones, including the one in Colorado who wanted to call me “Daddy” and the one in Reno with three sons by three different fathers who had never been married.

I might have gotten married in Colorado – to a different woman – in 1988, but I couldn’t let go of a promise I had made to someone who no longer even mattered to me. My first wife was a California girl, and when we got engaged in 1974, I had promised her that someday we would live in the Golden State.

It made perfect sense to me. She was from California and loved it, and I had been born in California and had always been obsessed with getting back. All through high school I had dreamed of sand and surf, and every time I heard the Beach Boys or Jan and Dean singing about cars, waves and the girls who were so tanned, I knew that was where I belonged.

But when my marriage fell apart in the late ‘70s, the one thing that went almost unspoken between us was that she thought I would never accomplish any of my goals. Even though I never saw her or spoke with her after 1982, a part of me wanted to prove that I could do that. Every career move I made, from Virginia to North Carolina to South Carolina to St. Louis to Colorado, had been with California in mind.

***

In the fall of 1988, two weeks after I met a very special woman, I was offered a job in Reno, Nevada – the next state over from the Promised Land.

I suppose I looked at California as a fresh start, a chance to live in a place where I had never screwed up or had anything bad happen to me. Along with all the songs and the movies, the beauty of the beaches and mountains, it meant achieving a goal I had been working toward for 10 years.

I knew I couldn’t have both the woman and the job, and she made it even more difficult for me by saying I shouldn’t turn a job down for her after we had known each other only a few weeks. That, she said, would put way too much pressure on her.

So I left, and although I still miss Colorado, I spent 18 months in Reno and then got a job offer in the Los Angeles area. Los Angeles hadn’t been my preferred destination. I was much more enamored of the Bay Area, and I fully intended to live in San Francisco instead of in the Southland. But the job I was offered was in the L.A. suburbs and it was there in 1992 that I finally realized what the purpose of my life was going to be.

Two years earlier, in December 1990, I had been through a shattering experience. I was driving south through Los Angeles on Interstate 5 when a truck decided to occupy the same space I was using. The driver sideswiped me and sent me spinning toward another truck, and all I could do was wonder how many times I was going to be hit. By the time I hit the guardrail and stopped spinning, the passenger side of my car and been crushed almost as flat as if it had been in a compactor.

I walked away from it, although I had a dislocated pelvis and a bruise that covered half of my left leg. The CHP officer who wrote up the accident report said it was a miracle that I had survived the collision. That got me thinking. I was 41 years old and hadn’t accomplished very much; I needed to decide as to what I wanted the rest of my life to be.

A few months later I went home and finally made peace with my father. We sat up and talked till 4 a.m. one night and cleared the air of almost everything between us, everything that mattered at least. He expressed his long-time frustration that for all the things I had done in rebellion, I was my own worst victim. I had been sort of like the firing squad that lined up in a circle.

“You always hurt yourself more than you hurt anyone else,” he said.

I had moved to Southern California for a job covering professional sports for a suburban newspaper. In the summer I wrote about Dodger games, in the fall it was the Rams and Raiders and in the winter I covered UCLA basketball and the Clippers. It was pretty much a dream job, and it kept me busy.

I nearly got married in 1991, even though I wasn’t really in love. It would have been a mistake, and it helped me realize that even if I was getting older, I didn’t want to settle for less than real love. Linda was from Wales, with a 12-year-old daughter and a 7-year-old son, and to be fair to her, I was more excited about being a dad than about being a husband.

I think she saw that, and she broke up with me by leaving a message on my answering machine. After that, I thought about moving back east to be closer to my family. My parents were retired, and two of my four siblings were living in the D.C. area. I started looking for jobs in the mid-Atlantic region, but nothing came up – and then everything changed.

I hit the gym in the summer of ’92 and worked hard to get into shape. I was coming to terms with the fact that I might be alone for the rest of my life, and I didn’t feel all that bad about it. I’d come home from work, watch a movie or two on the cable and then fall asleep. I don’t know if I was happy or simply numb, but I’m not sure it matters. I had my routine, and I was comfortable with it. I was writing a lot – four unpublished novels – and enjoying the fact that I could do it on a computer instead of just a typewriter.

***

Late that summer, I decided to dive into the dating pool again. I took out an ad in a singles magazine, and I met a woman I really liked. Then things got strange. To keep things from moving too quickly, she and I both decided to date some of the other people who had answered our ads.

I had two that interested me a little, a teacher in Pomona and a rocket scientist named Nicole in a town called La Canada Flintridge. The teacher was nice, but there was absolutely no chemistry between us at all. I met the scientist for lunch on a very busy Saturday – work in the afternoon and another date in the evening – and my whole world changed.

It was strange. We had almost nothing in common. She was an overachiever, and I … wasn’t. She had two doctorates, and I had gone through college on the 14-year plan. She owned a home and had two children – strangely, a 12-year-old daughter and a 7-year-old son – and I lived alone in an apartment. She was from France, here on a work visa, and I was an All-American guy.

She was lovely, though, and even though I had no idea why, she seemed to like me. We went out a couple more times – we both enjoyed movies – and after our third date, she said something I had never heard before. I had told her up front that I was dating someone else at the same time, and that I liked this other woman too.

We were sitting in her car in the driveway after a wonderful date. We had gone downtown to the Wilshire district to see “Gas Food Lodging,” and at one point when we were crossing the street, she seemed so happy that she skipped. This woman was growing on me.

But in the driveway, suddenly, things got serious. “I know you’re dating someone else too,” Nicole said. “And I don’t think you’re going to choose me. But I want to keep trying because I think you’re worth it.”

A month later, we were married and suddenly, I was a husband and a father.

I don’t know if anything was ever stranger – or more wonderful – than being a parent. After all, we were the generation that had gone to war with our own parents. When our folks told us to jump, we didn’t ask how high.

Instead, we fought battle after battle over the most trivial of issues. Why on earth did the length of our hair ever matter so much? I tried to explain it to my own son, but he takes so much for granted that I never did. He and I have fought about one-tenth as many battles as I did with my own father, but that’s more about him being comfortable in his own skin as it is about my parenting skills.

I have been so damn lucky. I have friends who absolutely worked their asses off trying to do the right thing for their kids, only to have things turn out badly. I know I have had a good effect on both of my children, but I know that they were almost parent-proof and were going to turn out to be special anyway. All I had to do was point them in the right direction.

Both kids made it through college with all sorts of honors, and Pauline is already a tenured officer in the U.S. Foreign Service. Virgile took some time off after college and trained for an Ironman Triathlon in France. A two-mile swim, a 115-mile bike race and a marathon run. Good lord, I pulled a hamstring just listening to him tell me about it.

He accomplished his goal – I knew he would – and then he got a job in the Foreign Service too. Both of my children are happily married, and Pauline has already given us a granddaughter, Madison Nicole, and a grandson, Lexington Wesley.

Nicole and I are getting near an early retirement – I’m actually “retired” already, thanks to the job market – and my wife is telecommuting from our new home in Georgia. Leaving and moving east was an easy decision. I will always love California, but it costs so much to live there, and the state has gotten so crowded.

It doesn’t really matter where we live, though, as long as we are together. I knew a long time ago that this woman and these two children had transformed my life into something more wonderful than I ever expected.

Love really has been about giving for me. My wife is bipolar, and our life together is often challenging. Don’t cry for me, though. Whatever I have given, I have gotten back tenfold from my beloved wife and my amazing children.

Mick Curran, my best friend since we met in the summer of 1965, has seen my life up close for three-quarters of it. He was there for the struggles and he’s seeing the sprint to the finish line.

He knows me as well as anyone.

“Mike has been my best friend for a long time,” Mick said. “He isn’t perfect – he can be petty, petulant and even cruel at times – but he is also kind, generous, funny, caring, unselfish and compassionate. He is in a word complex. We all are. We are all mixtures of good and bad, kind and unkind, selfish and other-centered.

“But what I like about Mike is that his life is defined by the positive aspects of his personality.”

It’s a nice testimonial, and in the end it’s probably the way I would like to be remembered.

I never became president or cured cancer.

I never played quarterback for the Redskins or center field for the Dodgers. I have yet to write the Great American Novel.

But in the only way that really mattered, all my dreams came true.

***

Note:

That was written in 2011 and put aside, and when I looked at it again, I found myself wondering if I really wanted to include a chapter about myself in a book about my classmates.

Then I thought, what the heck. I couldn’t have been a newspaper columnist or written novels if I didn’t think I had something to say. And I absolutely didn’t think I was looking at my life through the proverbial rose-colored glasses. I still haven’t written the Great American Novel, but I have had two published and other(s) on the way.

More important, I still have Nicole, Pauline and Virgile and their spouses and I have six grandchildren.

Life may not be perfect, but it is certainly good.

When it comes to love, Nicole has given me more than I deserve. And in the end, the love you take really is equal to the love you make.