Someone I don’t know, someone named Susan B. Davis, posted the following anecdote on Facebook:

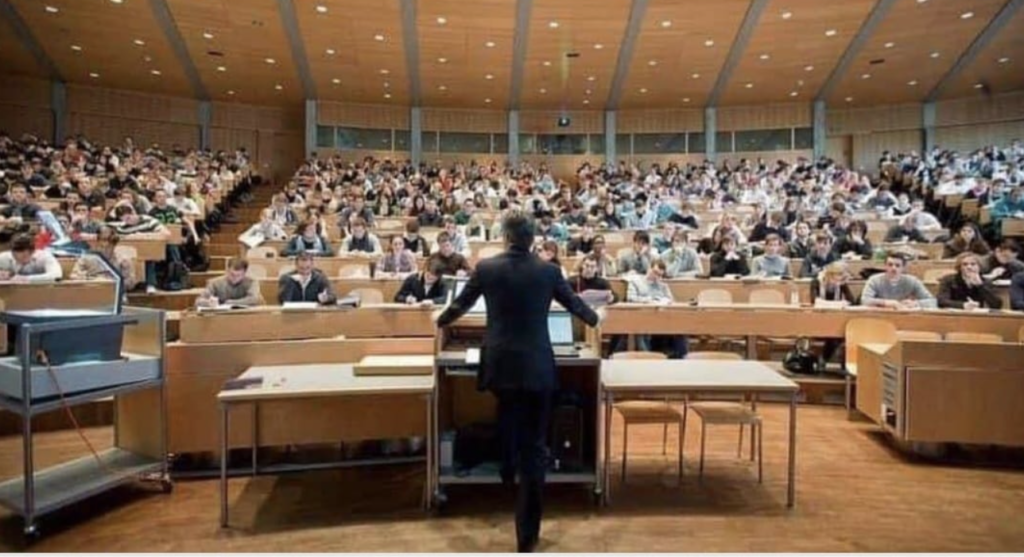

The professor enters the lecture hall. He looks around.

“You there in the 8th row. Can you tell me your name?” he asks a student.

“My name is Sandra,” says a voice.

The professor tells her, “Please leave my lecture hall. I don’t want to see you in my lecture.”

Everyone is quiet. The student is irritated, slowly packs her things and stands up.

“Faster please” she is asked.She doesn’t dare to say anything and leaves the lecture hall.

The professor keeps looking around. The participants are scared.

“Why are there laws?” he asks the group.

All quiet. Everyone looks at the others.

“What are laws for?” he asks again.

“Social order” is heard from a row.

A student says, “To protect a person’s personal rights.”

Another says “So that you can rely on the state.”

The professor is not satisfied.

“Justice” calls out a student.

The professor smiling. She has his attention.

“Thank you very much. Did I behave unfairly towards your classmate earlier?”

Everyone nods.

“Indeed I did. Why didn’t anyone protest? Why didn’t any of you try to stop me? Why didn’t you want to prevent this injustice?”

Nobody answers.

“What you just learned you wouldn’t have understood in 1,000 hours of lectures if you hadn’t lived it. You didn’t say anything just because you weren’t affected yourself. This attitude speaks against you and against life. You think as long as it doesn’t concern you, it’s none of your business. I’m telling you, if you don’t say anything today and don’t bring about justice, then one day you too will experience injustice and no one will stand before you. Justice lives through us all. We have to fight for it.

“In life and at work, we often live next to each other instead of with each other. We console ourselves that the problems of others are none of our business. We go home and are glad that we were spared. But it’s also about standing up for others. Every day an injustice happens in business, in sports or on the tram. Relying on someone to sort it out is not enough. It is our duty to be there for others. Speaking for others when they cannot speak for themselves.”

*****

Right about now, some of you — the ones who haven’t already quit on the story — are asking me if there is a point to this story.

Believe it or not, there is, although I think the professor is at least partly wrong in his conclusion. I suppose it is true that the students didn’t protest because they weren’t personally affected, but I believe fear was a much greater motivation. When someone in a position of authority behaves erratically, a far more normal reaction is trying to do nothing to make that person notice that you even exist.

After all, it’s almost a no-win situation.

Unless you figure out that the entire scenario is staged and the professor and Sandra are in cahoots to make a point. If that’s the case. you can protest and have a good story to brag on for the first of your life.

“See what a good boy/girl I am/was,”

Fifty-seven years ago this month, when I was starting my senior year of high school in Virginia, I was involved in a similar moment. At the beginning of the school day, we met in our home rooms primarily for the purpose of taking attendance and listening to announcements.

I’m not sure how the subject came up, but September 1966 was the first month our school was truly integrated. A year earlier, there had been only four black students in our school and two of them were basketball players. Now there were 300, about 10 percent of the student body.

Our home room teacher taught German, and at age 16 with Jewish relatives, I was hardly a fan of the Aryan side of my ancestry.

For some reason, our teacher went on a rant in front of her all-white class. She said black people didn’t want to work for anything and just wanted to be given things for free.

The class was stunned. I’m sure most of them didn’t agree with her, but what can a high school senior say that wouldn’t cme back to hurt then later. And many of the kids in that class had fathers in the military.

The expected response to an adult was short and sweet.

“Sir, yes sir!”

Except for one kid who was at war with authority. Without even raising his hand for permission to speak, he blurted out one sentence.

“That’s a really racist thing to say.”

Someday he would learn the difference between things you say out loud and those you keep to yourself, but not on this day in 1966.

She already hated him.

Now it was even worse.

“This is why you’ll never be in the National Honor Society. The teachers all hate you.”

Actually, he wanted to tell her, that’s not entirely accurate. Not all the teachers hated him, and most of the ones who did, it was because he was an underachiever. Someone who could score nearly 1400 on his SATs and be a National Merit Scholar, but just barely maintain a B average.

He was voted Most Likely to Underachieve.

At least he did what the students in the anecdote should have done.

He spoke up against evil.