“Growing up happens in a heartbeat. One day you’re in diapers, the next you’re gone. But the memories of childhood stay with you for the long haul.”

Most of us lead three lives.

There’s the first one, the one described in the above quote from “The Wonder Years,” although it’s more than memories that stay with us and childhood doesn’t end at the same time for everyone.

Some kids are grown at 16, others when they finish high school or college. Some never get there, at least unscarred.

The second life is adulthood, when we make our mark on the world for better or worse. It ends when we allow it to, or when it is forced on us.

The third and final one is retirement, when we enjoy the results of our years working and look back at the things we did and didn’t do. The idea there is that if you have provided well for retirement, you can enjoy life within the limitations of your aging mind and body.

My own childhood lasted far too long. I don’t know why, and I really have no one to blame but myself, but I grew up frightened of so many things. My talents were things I didn’t value enough, and what my fraternity brother Lee Strang would later refer to as “social skills” were definite weaknesses.

Puberty came late and my driver’s license came later. I was fighting the stupidest war with my parents. They didn’t let me get my license when I turned 16, so I turned down the chance to get it at the beginning of my senior year. That meant I didn’t date at all, and getting my license two weeks before the prom only meant my date would be someone who didn’t mean anything to me at all.

She was a nice girl, quite pretty, and we had done some community theater stuff together, but the Woodson prom was our first and last date. She had one very interesting quirk. She spoke with an English accent even though she had never been to England and her family wasn’t English. She said it was because she had 11 siblings and wanted to stand out in some way.

I wish I had thought of that. I probably could have done a good Mexican accent.

Seriously, though, when I finished high school I was 17 going on 9. When I left for college in September I was not only a virgin, I had had only four dates in my life and other than a sip of my grandfather’s beer once when I was much younger, I had never tasted alcohol.

So of course the University of Virginia, party school extraordinaire in the late ’60s, was where I started my 14-year on-and-off journey through college. My first roommate was a kid from the Tidewater area who claimed he had sex 200 times in high school.

Hell, so did I, but not with other people.

Social problems might have been the most visible for me, but I had so many other things going wrong that weren’t as obvious. I had become the prince of passive-aggressive, and as unhappy as I was with the way things were going in my life, I never even thought about breaking the mold and doing things differently.

After I had flopped at two colleges, mostly by not going to class and not taking exams, it never crossed my mind to save a few hundred dollars and take off for Texas or California and get a fresh start. Instead I stayed in the same nest I had fouled again and again and kept making the same mistakes.

I didn’t marry the first girl who was nice to me, as some guys do. I married the second one, and within four years the marriage was a shambles. At least by then I was starting my career, even if I probably did pick the media equivalent of the buggy whip industry. Newspapers were already starting to disappear, and I remember thinking that if the industry would only survive till 2015 — when I reached retirement age — that would be all right with me.

But even though I wasn’t terrified by the choices ahead of me, I was certainly timid. In April 1980, faced with a choice between a full-time job at a small daily paper and a part-time job at the Washington Post, I made the safe choice and probably limited my career from the start.

If I had gone to the Post, I could have learned what it takes to work at a special paper — even as a part-timer — and I could have made contacts that would have helped me down the line.

In fact, my career didn’t go all that badly until I started making really bad choices in 1988. I have written before about living too long with the same dream and not being willing to give up on it when something better came along.

I was living in Colorado and working as sports editor of a small paper. I loved it there, but I moved on every couple of years and I was still trying to work my way west. Going to Reno for 18 months was a mistake, and career-wise, so was going to Ontario in the suburbs of Los Angeles in 1990.

I took a $5,000 pay cut to go to Ontario, but my plan was to get into the L.A. market and then start looking for another job within a year.

It never panned out. The job market in Southland newspapers dried up in the early ’90s and never got better. Of course by late 1992 my priorities had changed and family — in the form of a wife and two children — was at the top of the list.

It wasn’t the end of my fears, but somehow I was beginning at least to know why I was frightened by so much. When I was a little kid, people always seemed to be telling me how smart I was and how I would accomplish great things in this world.

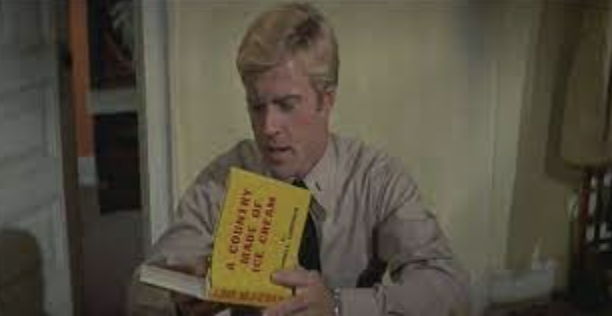

And when I was really young, things came too easy to me. It was as if I lived in a country made of ice cream. When things got more difficult and I couldn’t just succeed automatically, I didn’t even try. Saying I didn’t care was easier for me than explaining why I had failed.

The word “underachiever” seemed to fit me perfectly.

I was a National Merit Scholar in high school, something that basically comes from taking a standardized test. At that time, Michigan State was recruiting from that group in a big way. I hadn’t had any desire to go there, but I figured if they wanted me, I would apply.

When they saw my great tests scores with my B to B-minus grades, they rejected me. Indeed, the letter said in so many words that I was exactly the kind of student they didn’t want — an underachiever.

I was so smart, but the number of A’s I got in subjects other than Band and Phys Ed in high school could have been counted on, well, zero fingers.

If I didn’t try …

I don’t know if we get more than one life, but I know I don’t want another one with the aggregation of strengths and weaknesses I’ve carried through 65 years of this one.

Give me average intelligence and physical abilities if you must, as long as I can combine them with courage and an indomitable spirit.

Not a country made of ice cream, but one made of iron.