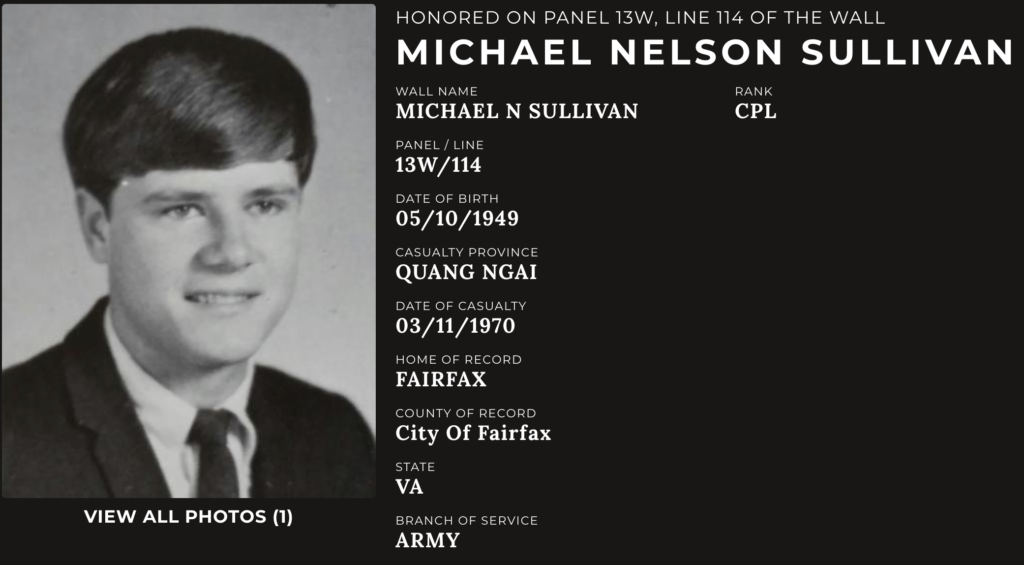

Jon Rumble was not the only member of our graduating class to be killed in Vietnam. Jon was better known because of his activities with the Drama Club. Mike Sullivan only went half days in 12th grade, working in the afternoons.

But he had friends too, and he had a reputation as a very nice person. He died of a fluky accident doing his job as a medic, two months before his 21st birthday.

Here’s his story, written in 2009.

FORTUNATE SON

Mike Sullivan was no senator’s son, but he carried himself with pride, did his duty and enjoyed life for as long as he could.

When the male members of the Class of 1967 graduated from Woodson, most of them had two choices.

College – or Vietnam.

In a class of more than 800 people, many of whom scattered to the four winds after graduation, no one really knows exactly how many members of the Woodson Class of ’67 served in that controversial Asian war.

We know Mike Scott and Mike Willis served and returned, and we know Mike Beall died in an Army training accident at age 18 while preparing to go to Indochina.

Then there are the two names on the Wall.

Many of us knew Jon Rumble, who had made his mark despite spending only his senior year among us. He had played the male lead in the senior class play and had made many friends.

We didn’t know Mike Sullivan as well. Other than his senior picture, the only other shot of Mike in the yearbook is as one of the students who participated in Distributive Education, going to classes in the morning and leaving at noon to go to work.

If there’s one thing many of us have learned over the last 41 years, it’s how few people we actually knew in our class of 804 seniors in a school of 3,300 students. If we didn’t share classes with someone, the only way we knew them was either from after-school activities or from our own neighborhoods.

Kids who spent only half a day at school – kids who weren’t in band or clubs or on athletic teams – weren’t as well known. So while plenty of us in the Class of 1967 remembered Jon, not as many knew Mike all that well.

One who did was Randy McDaniel, who grew up right across Route 236 from Sullivan.

“We played a lot of sports together at the YMCA.” McDaniel said. “His dad worked for the government and my sister carpooled with him. She told me that at one point while we were in high school, his dad actually blocked incoming phone calls because too many girls were calling for Sully too late into the evening.”

Of course, that was hardly the worst problem for a teenage boy to have.

Randy went through 11 years of school with Mike, and during grade school, junior high and most of high school, both hung around with Butch Fagot, Hap Hodges and Willard Totten. They all spent a lot of time playing sports together.

“Sully was a very fast runner, although not as fast as Hap,” Randy said. “He was very fun loving and extremely witty.”

We know that he was 20 years old when he arrived in Vietnam and that he was married. And we know that he died there.

***

Jim Regn was one of Sullivan’s best friends, and nearly 50 years later, he still remembers the evening they met.

“We both delivered newspapers for a Washington daily,” he said. “I was waiting at the driveway for Mr. Manning, the district manager, to show up and collect the subscription money collected from the customers on my paper route. He would often take one of his carriers with him for company and to meet the other kids. You would get to ride around in his panel truck and get dinner at Topps or McDonalds.

“That evening he arrived with Mike, a kid who was wearing a baseball hat I recognized as a Fairfax County Little League Eastern Division team. East and West divisions were divided by Ox Road. In those days every kid that played baseball wore his hat everywhere. By it you could tell if a kid played for a good team and on what side of the county he lived. Since I lived on the west side I didn’t think Mike and I would likely run into one another beyond the occasional newspaper connection.”

A year later, Regn and Sullivan found themselves in the same home room at Sidney Lanier Intermediate. Since teachers had a tendency to seat their students in alphabetical order, the two boys often found themselves within “talking distance” for a good part of the day.

“Mike was friendly and funny; he had charisma,” Regn said. “I wanted to be his friend. In English class our equal distractions developed into collaborations on ridiculous stories written more for the amusement of ourselves than completing the English assignment. Mike Schmidle must have had a similar background, because when the three of us got to Mrs. (Lorraine) Gorey’s English class at Woodson we fell right into the same practice using Dylan’s LP liner notes and John Lennon’s books for inspiration.”

It took them a while to get together in high school. Regn didn’t live in Woodson’s district and spent his freshman year at archrival Fairfax High. The two boys talked on the phone to keep in touch, but didn’t see each other very often.

In the spring of 1964, though, Regn’s family moved into the Woodson school district.

“Our friendship became a fixture,” he said. “We spent the summer hanging out at the YMCA pool but also doing some gainful things.”

He remembers that Sullivan always seemed to have a job, and that anyone who wanted to spend time with him pretty much had to work too.

“But the way he did it was more like fun, or at least funny,” he said. “Sully was a performer with a likeable, easy manner. We pumped gas and customers loved him. We would caddy at the country club and golfers wanted him to carry their clubs. We worked at Bernie’s Pony Ring at Bailey’s Crossroads and kids having Wild West birthday parties needing a sheriff or bad guy were delighted when he got right in with them playing the role. He was comfortable with kids and enjoyed making up cowboy names like Tex and Cimarron to give them as he led the ponies around the ring.”

Regn remembers that it wasn’t so much about earning money as it was simply wanting to keep busy.

“The pay just added options, and he liked to be generous,” Regn said. “One Saturday morning we were caddying at the Fairfax Country Club and one of the two guys he was caddying for got a hole in one. At the end of the round, the guy gave Sully a huge tip. We usually carried two bags each in the morning and two each in the afternoon. But that day, he shared the tip, giving me what I would have made working that afternoon. We snuck away early and hitchhiked to Fairfax to catch the bus to Seven Corners.”

As sophomores, both boys tried out for junior varsity football. Sullivan had been one of the stars of the freshman team. His position was assured. Regn had never played on a team and was apprehensive.

“With his encouragement and wanting not to be left out, I went along and made the team,” Regn said. “I even got a starting position as a lineman which, at that level wasn’t hard if you would just hit, block and tackle. But it was his show. He was a running back and receiver with speed, awareness and maturity. It really was amazing to see the plays he made. He was graceful and made it look easy and natural, like a pro.”

***

By all accounts, Sullivan enjoyed himself and did pretty much what he wanted to do.

That included not going out for football again after his sophomore year, something Regn still wonders about more than 40 years later.

“I don’t know why he didn’t go out for varsity,” Regn said. “He was sure to have made it. I’ve thought some in recent years that maybe he knew I wouldn’t have made the cut and his decision was a courtesy to me. I don’t recall ever asking him about it. We had driver’s licenses by then and we got interested in other things.”

There were parties, various jobs, get-togethers at Washington restaurants and trips to the beach that wouldn’t have been possible with football practice every day. Regn thinks maybe they allowed their “less good instincts” to prioritize and arrange things so that they could have more fun. “It probably would have been better if football had been more important,” he said.

For whatever reason, they didn’t play.

The last two years of high school passed quickly, and graduation brought the very real threat of being drafted front and center. Neither boy had any intention of using student deferments to dodge the draft, but they did spend a year at Northern Virginia Community College trying to figure out what they wanted to do.

“In the summer of 1968, Sully had an apartment off Duke Street in Alexandria,” Regn said. “His popularity made it a busy place night and day. Sully worked full time and usually left the door unlocked for friends to stop by for food or drink. Just put back what you took when you can was the house rule. Most evenings were a perpetual open house with all sorts of people dropping by.”

Some of the other tenants in the building were young soldiers stationed at various local military installations, and Sullivan and Regn were hearing first hand information from guys just back from Vietnam and the Tet offensive earlier in the year.

“Sully liked GIs and got along well with them,” Regn said. “They had money and fast cars and Sully admired both. More than a few times we all went into Georgetown together and ended up crashing in the empty bunks in the 3rd Regiment barracks at Fort Myer when we couldn’t quite make it back to Duke Street.”

They were keeping busy, having fun but knowing all the while that time was running out; the war and the draft were always there.

***

By August 1969, Regn was in Vietnam. Sullivan arrived three months later. The two best friends had hoped to be stationed near each other, but Sullivan was assigned to the 11th Light Infantry Brigade at Duc Pho, while Regn was 300 miles to the southwest with the 1st Cavalry Division.

Sullivan took pride in the fact that he was part of the 4th battalion, 3rd regiment of the 11th Light Infantry. That unit is known as the “Old Guard” and was originally assembled by George Washington himself during the American Revolution.

The unit’s home is Fort Myer, so Sullivan knew that once he completed his time in Vietnam, there was a good chance he would complete his service obligation only 15 miles from home.

“We kept in regular contact by Army in-country letters,” Regn said. “His were always positive and decorated with drawings and funny remarks. I somehow managed to save most of them, each one stained red from sweat and the laterite soil the place was made of. We wrote about what we were doing or news we had learned from back in the world. Mostly we talked about all the things we would do when we got home.”

For most of his time in country, Sullivan was excited about returning home to his wife. He had learned soon after arriving in Vietnam that she was pregnant, and his letters to Regn would ramble on with hope and plans for the future.

“He would make suggestions for my involvement as ‘Uncle,’” Regn said. “His enthusiasm was infectious. I don’t remember exactly what I wrote in return, but I must have wanted in on it, as he kept them coming. After all of my careful re-readings only once is there the now sad bid for agreement that those things would actually happen.”

A lot of dreams died in Vietnam. There are 58,195 names on the Wall – most of them fathers, sons, brothers, husbands – and it’s a fair bet that nearly all of them spent time in Vietnam thinking of what their lives would be like when they returned home.

Sullivan was in Vietnam only for a few months, but he made his mark. Regn says he talked to others in his company who said he was always cheerful and steady, “just the kind you want around in serious circumstances.”

For the first three months of his tour he was a rifleman, often volunteering a share of the duties involving more than the usual risk.

“He was proud when he was awarded the Combat Infantryman’s Badge, which signifies meeting a required amount of contact with the enemy,” Regn said. “Of any collection of veterans, there wouldn’t be but a handful of guys authorized to wear it.”

When attrition hit his company and created a need, Sullivan volunteered to become a combat medic. At age 20, he was doing a job not many anywhere could or would do.

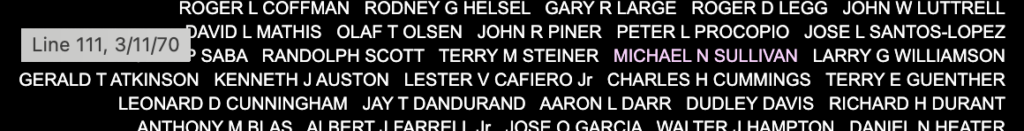

Regn says that March 11, 1970, started out like most days in Vietnam. Attack helicopters that provided transportation and fire support for Sullivan’s company had been busy engaging targets identified during the night.

The dry season was coming and the numbers of North Vietnamese and organized Viet Cong were increasing in the battalion’s area of operations. The mission was to locate and destroy enemy units while providing security for the civilian population. Evidence of enemy activity such as slick trails, bunkers and weapons and supply caches was obvious and contact was becoming more frequent.

At that time, practically every American unit in the country was under strength and Sullivan’s D Company was no exception. Before noon that day, two men were medevaced out for non-combat injuries and malaria.

It turned out that a battalion-size unit of the North Vietnamese army was using a nearby mountain as a base to gather resources from the local population and launch combat operations against American and South Vietnamese. As the day progressed, the tempo of action was picking up.

D Company discovered a bunker complex with a large amount of weapons, ammunition, medical supplies and food. They destroyed the ordinance and sent the food and medicine to the rear for distribution to the civilians around Chu Lai. While this was going on, a medevac helicopter was hit by enemy fire and crashed.

Sullivan and others were sent in to secure the downed chopper as soon as they could get clear. When they reached the crash site, they set up a night defense position to guard the crew and the chopper.

About two hours after dark, their position was hit from three directions by small arms fire, rocket propelled grenades and mortar fire. Shrapnel from one of the RPGs hit Sullivan and killed him instantly.

“The following combat action was so intense that the two medevac choppers that responded to the call for assistance were shot down,” Regn said. “The pilot of a third chopper was wounded while trying to get in for an extraction and couldn’t land. The area was just too hot to get choppers in to pick up the dead and wounded.

“Sully’s friends spent five hours carrying him in a stretcher made from a poncho through the rain, down a rocky, slippery stream bed to where a helicopter could land to pick him up.”

Ironically, the final entry in the brigade’s daily journal describes the action of March 11, 1970, as “light.”

Jim Regn was at Landing Zone Buttons when a radioman asked him if he knew Mike Sullivan. He said Sullivan had been killed in action and Regn had escort duty to return with his body.

“On my way back to Phouc Vinh, I was hoping maybe it was a mistake, that it was another with the same name,” Regn said. “I was stunned and didn’t want to believe he was dead.”

When he read the orders and saw that the final destination was a funeral home on Backlick Road in Springfield, he knew it was his friend.

“At the time a request could be made by the family of the deceased for a friend also serving in country to be the escort,” he said. “Sully’s family wanted me to have the honor and I’m grateful for it.”

Regn didn’t catch up with Sullivan until he reached the military mortuary at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. Because of the distance between their units and the difficulty the Army had in locating him, Regn was a few days behind in transit.

When he arrived in Delaware, a sergeant who had recently returned from a tour in Vietnam with the First Division led him through an aircraft hanger with dozens of bodies in various stages of repair. They located the casket and carefully loaded it into the hearse for the long drive to the funeral home. They drove down into Maryland and hit Route 50 just east of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. While they crossed it, Regn found himself thinking of the many times he and Sullivan had made the trip to and from Ocean City, with or without dates, with or without money.

“It didn’t matter,” Regn said. “We always made it fun.”

On that final trip, it was the sergeant and Regn in the front seat and Sullivan in the back in a flag-draped coffin. He doesn’t recall seeing any acknowledgement or respect from others on the road that day as portrayed in some recent movies about the subject. That didn’t happen until the casket arrived in Arlington, back with The Old Guard.

For the last 40 years, Sullivan’s home has been Arlington National Cemetery, about 15 miles from where he grew up and attended high school. His grave is located down the hill on the west side of the Mast of the Maine Memorial. Facing his marker, looking just to the right, you can see the Custis-Lee Mansion. A glance to the left across Jackson Circle past the brown stone fence yields a view of the barracks of the 3rd Infantry Regiment.

Regn says the setting is beautiful, worthy of the life his friend led and hoped to continue.

“The elegant landscaping and quiet dignity of the place makes the incoherent din from across the river hardly noticeable,” he said. “Each time I go, I’m inspired to appreciate what I know were Sully’s ambitions, things that I’ve come to believe are as important as anything else in life.

“He wanted to be a good father, a good soldier, a good friend. All of these things he did by deed or example.”