From 2009, the story of one of the truly outstanding people in our class.

LET TIME GO LIGHTLY

For class president and naval officer Mike McCuddin, old friends are the best kind of friends, because they knew him then and they know him now.

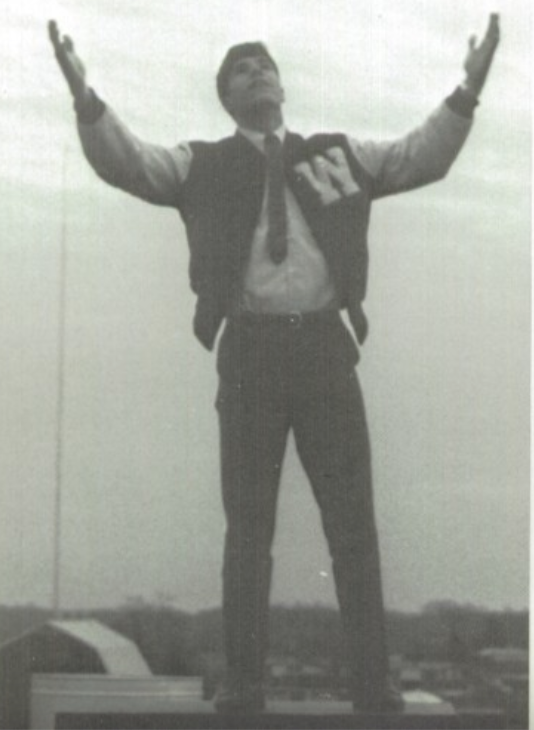

To any casual observer, Mike McCuddin would come across as one of the golden boys of the Class of ’67. His senior yearbook entry lists him as class president as well as a member of the varsity football team, the National Honor Society and the Key Club.

McCuddin made friends easily. He says he liked most people, and even the ones he didn’t, he could usually find something to like about them. He radiated the confidence of a kid who had it all together, a young man who understood himself and knew where he wanted to go and what it would take to get there.

Many of the friendships he made in high school have lasted until this day.

“Some of my best and closest friends were my classmates at Woodson,” McCuddin said. “They’re the people I most trust. We weren’t very good at covering up our character back then. We became much more proficient at disguising ourselves and putting up layers of protection as we got older.

“But when you meet someone you knew in high school, the facades seem to drop away pretty quickly. You can see through the cover-ups and barriers that we all learn to put up, and they know it. The real person, hidden inside, comes out. Either they’re a real friend – or they’re not. And if they’re your friend, you will never have a better one.”

***

Michael Ennis McCuddin was good-looking and popular, intelligent and outgoing. His good grades and his athletic ability paid off for him with a presidential appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy, and within less than a month after graduation, he found himself in Annapolis, Md.

Do you remember the transition from high school to the next part of your life, the shock at realizing that people have all of a sudden stopped treating you like children? Sometimes it’s as simple as seeing that the restrooms no longer say “Boys” and “Girls,” and sometimes it’s as complicated as realizing that you are responsible for yourself and your behavior in a way you never were before.

It can be especially awkward for boys, this transition from being considered a kid and being viewed as a man. For some it happens slowly, living at home during college and still being under the watchful eyes of parents. But for others it happens so quickly it leaves them dazed and wondering where – and who – they really are. At a time when many young Americans were beginning to question our military and its role in the world, before he had even reached his 18th birthday, McCuddin was reporting for duty.

On June 30, 1967, he found himself standing in formation with 2,000 other young men, raising his right hand and swearing to defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic.

“All of a sudden, I was in the U.S. Navy,” he recalls. “I was just 17 years old.”

In some respects, his decision was probably foreordained. While many members of the Class of ’67 came from military families, McCuddin’s father Leo had been a naval aviator, a flying ace in World War II, and eventually rose to the rank of Rear Admiral.

“Some of my earliest memories involve playing with models of Navy jets,” he said. “My father had models of the planes he was flying after the war. These weren’t the models you put together from a kit. They were the ones made by the aircraft manufacturers to advertise their planes.”

They weren’t flimsy. They were the kind of models that could take a beating, the kind a kid could play with for hours without doing much damage to them.

“They captured my imagination,” McCuddin said. “They were beautiful. Flying a plane like that, at the speed of sound, chasing down the bad guys – could there be a more thrilling job than that?”

It wasn’t just the planes. Anyone who has seen movies like “Top Gun” knows that the men who flew them, like McCuddin’s father and his friends, could be as exciting and entertaining as the planes they flew. They were great role models for young Mike, and he still recalls them 40 or 50 years later.

“They were proud, confident, adventurous,” he said. “They told stories that kept you on the edge of your seat and jokes that made you laugh so hard you couldn’t breathe. These were men who didn’t need to brag. What they did and how they carried themselves told you everything you needed to know about them.

“No one questioned their ability, or character, or courage. They had a zest for life that I have never seen in anyone else. They were the best and I wanted to be one of them.”

So he worked for an appointment, hoping to follow his father and his friends into the air. But as McCuddin neared the end of his high-school years and became more aware of the world, he started to see that life wasn’t as simple as it might be in an aerial dogfight.

“My admiration for those men has never faded,” he said. “But I could see where they were sometimes caught in the middle and found themselves in very bad situations.”

By the end of 1965, with the Class of ’67 halfway through its junior year, the war in Vietnam was in full swing. There were 200,000 Americans in country, with many more to come in the next few years. The Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964 had spurred the buildup, but there was little progress to cheer American audiences.

“Our military had been sent over there to do a very difficult and dangerous job,” McCuddin said. “Many of them had been drafted and sent to a part of the world they had never heard of, for reasons that were far from clear. They were being told to make the ultimate sacrifice in a war that often times didn’t make any sense. I could understand why many in and out of the military were very unhappy with the situation our country found itself in. It was in those circumstances that our high school lives ended, and it was time for me to take the next step.”

When his letter of acceptance came, his parents were thrilled for him. They encouraged him to take advantage of the opportunity – a free education at one of the finest schools in the country with a guaranteed job to follow – but they understood the depth of the commitment that would be required.

“They made it clear that it was my decision, and I shouldn’t go unless I was sure that was what I wanted to do,” McCuddin said. “In fact, I wasn’t sure that was what I wanted to do, but this was a difficult opportunity to pass up. My friends, who were getting ready to graduate from high school with me, were supportive, but they were concerned that the Naval Academy was not the place for me.”

Jim Colvocoresses, one of McCuddin’s two closest friends to this day, remembers the time.

“Mike, Loren (Piller) and I were great friends throughout high school and almost constant companions in our early years at Woodson,” he said. “We lived in the same neighborhood and were all military brats with all the things in common that come from that experience. All three of our fathers were senior officers whom we respected very much, so the thought of following down that career path seemed a completely natural course to us, Vietnam notwithstanding.

“Mike was the only one of us who really had a shot at the very competitive military academy entrance requirements and he worked his butt off to make it happen on the athletic, academic and civic leadership fronts expected of serious applicants. I think Loren and I were almost as happy as Mike when he got his appointment letter.”

As badly as he had wanted it, the decision was still a difficult one given the times.

“The clock was ticking,” McCuddin said. “I had to make a decision to go or not to go.”

He chose Annapolis, and he excelled there the same as he had in high school, becoming president of his class. He had intended to follow his father into aviation, but all that studying had cost him his 20-20 vision, so he couldn’t pass the flight physical and couldn’t become a pilot.

Flying in the second seat was still a possibility, but McCuddin had done that several times during the summers while at the Academy and hadn’t enjoyed it all that much.

“It was pretty wild stuff,” he said. “The flights were very physically demanding; there’s nothing like a 6-G dogfight to wring you out. I liked the idea of flying fighter jets, but I didn’t want to be the guy in back being jerked around.”

He had majored in oceanography, and he had been elected president of his class three times. When he graduated in 1971, he chose surface ships as his specialty and was assigned to the USS Pratt, which was based in Florida and spent most of its time cruising in the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea.

McCuddin didn’t much care for duty on a destroyer – “Not enough excitement, I guess,” he said – so after two years on the Pratt, he was looking for something different. He became a Navy diver on a salvage ship based in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Being a diver turned out to be a great experience, and after a couple of years, he had a positive outlook on the Navy and was ready for his first “shore duty” as a Naval ROTC instructor at the University of Idaho in Moscow, Idaho.

During his three-year tour there, he got a Masters Degree in Fishery Resources. At the end of that tour, he considered leaving the Navy.

“I enjoyed teaching and the salvage Navy, but they wanted to send me back to destroyers and I didn’t want to do that again,” he said.

He had completed his obligation to the Navy by that point, so his choice was whether to leave and do something different or continue on and make a career out of the military. He had pretty well decided to leave when a conversation with one of his NROTC students changed his mind.

The student – one of McCuddin’s best – had finished his first summer cruise and knew he didn’t want to serve either on surface ships or submarines. He wanted to fly, but less-than-perfect vision disqualified him from becoming a pilot. McCuddin didn’t want to lose him, so he recommended the Naval Flight Officer program. NFOs fly as part of crews on several types of planes, where they fill roles as bombardiers, navigators or radar intercept officers, to name a few.

One of the more interesting possibilities in the NFO program was to fly in a P-3, a four-engine aircraft with a crew of 13 that searches for submarines. An NFO on a P-3 could be the mission commander and the tactical coordinator, planning search patterns, deciding where the aircraft would fly, where to drop sonobuoys and where and when to attack enemy submarines.

His student seemed very interested in P-3s and agreed to stick around long enough to find out more about them. After the student left his office, McCuddin found himself wondering why he had never considered being an NFO in a P-3 himself.

“It was a little late in my career to switch specialties (from surface warfare to aviation), but I felt I had to switch or leave the Navy and start a different career,” he said.

He applied for flight school, was accepted and went to Pensacola, Florida. After a year of training, he was assigned to a P-3 squadron operating out of Barbers Point Naval Air Station in Hawaii.

“It was a great job,” he said. “I ended up staying in the Navy for 20 years. A lot of that time was in Hawaii, but I was also stationed in Puerto Rico and traveled around South America and West Africa, working with the navies of 24 countries on those continents.”

He retired in 1991 with the rank of commander and moved to Washington State with his wife Wendy. He has become part of a Woodson ’67 contingent in the Pacific Northwest that includes Bruce Cook, Carol Costantino, Bob Douthitt, Robin Gohd, Marna (Podonsky) Hanneman and Helen Roberts in Washington, Carol (Giller) Gajdosik in Montana and Don and Raleigh (Shreve) Orth in Idaho.

The McCuddins settled in Port Orchard, a town of about 7,700 just south of Bremerton on the western side of Puget Sound. It has a small-town atmosphere despite being almost in the shadow of Seattle across the water. It’s the first time McCuddin has lived in one place for any length of time – Navy brats and Navy officers both move around a lot – and he has become involved in both environmental and growth issues in the community.

“It is frustrating at times,” he said. “But we are trying to come up with a plan that makes sense for the area and preserves the best natural features while still accommodating growth.”

Being retired from the Navy at age 42 doesn’t mean the former class president is sitting on his porch watching the world go by. He works as an adjunct professor at Tacoma Community College, teaching classes in Oceanography and in Environmental Science, and he works weekends as a rafting and kayaking guide.

That one sort of came out of the blue.

“I was looking for new things to try, things that I had always wanted to do but had never been in the right place at the right time for,” McCuddin said. “I saw an ad in the paper – ‘Whitewater Rafting Guides, will train’ – and I thought I would give it a shot.”

It turned out to be great fun, and it expanded into sea kayaking in warm weather and snow-shoeing and cross-country skiing during the winters.

It’s enough to keep him busy, not to mention in shape, as he approaches his 60th birthday. It has also made him very popular with those classmates who live in the Pacific Northwest.

For the last six or seven years, McCuddin and Helen Roberts have worked to put together annual mini-reunions on summer weekends, and rafting and kayaking have become a popular part of those get-togethers.

“It has been a great way to stay in touch with old friends,” he said.

Bob Douthitt, who lived in Seattle for some time and then moved across the state to Spokane, says he has come to know McCuddin much better through the weekends than he ever did in high school. As seniors, the two of them practically ran the school, with McCuddin the class president and Douthitt the student government president, but they never had any classes together.

“We were in Key Club together,” Douthitt said. “And I think we walked a few miles together on a Saturday during a fundraiser for a radio station, but otherwise, I knew him primarily by reputation.”

The reunions changed all that.

“It’s like he has been the dad and Helen has been the mom,” Douthitt said. “Helen has usually taken the laboring oar in organizing things, pinning down dates and locations, contacting people, stuff like that. Mike, on the other hand, has brought equipment (rafts some years, kayaks other years), gotten us to agree on what time to show up somewhere, shown us how to put on wet suits and life vests, stressed safety tips and checked to see whether knots were tight enough.”

It’s the same quality of organization, of making sure everything got done properly, that made McCuddin a success in the Navy.

“It’s interesting to see how people in their late fifties spend their time and what interests they’ve developed, and then wonder whether there were any hints 40 years ago when you knew them in high school of what they’re doing now,” Douthitt said. “In Mike’s case, he loves the environment and the outdoors (plus I think likes the equipment care and maintenance that goes along with it), likes teaching and dealing with the students, enjoys golf with his wife Wendy, likes taking a few risks here and there (just from the nature of his hobbies, if nothing else), but is also pretty disciplined (i.e., hasn’t put on much weight).

“Likewise, you can tell from the way his eyes move around the room and he checks his watch while trying to enjoy a leisurely cup of coffee at breakfast that he can’t resist his sense of responsibility for making sure whatever event he’s planned comes off right, and all of us have appreciated that.”

Douthitt continued: “The sense of responsibility, discipline, playful risk-taking, and outdoor, athletic aspects are each traits that were clearly always there. But when I think of the vivid image in his graduation speech of a little orphan girl in Vietnam, homeless and hungry, and how surprised I was at first when he made that point — since he was about to start Annapolis, and so many of us were from military families, and there wasn’t even much of an antiwar movement started then anyway — I remember that his point was one of humanitarian concern, rather than a political statement. Mike’s always had a soft spot for those who can’t help themselves very much, so it makes total sense that he would like to teach, and also help preserve and enjoy the passive planet we inhabit.”

***

Did McCuddin question himself and the decisions that shaped his life when he came out of high school?

Of course he did. He was too smart not to wonder, not to study various options. There were many like him, just as there were many on the other side of the divide that started back then and has split America until this day.

Get to know someone of our age even now and eventually you’ll learn where they stood on the war in Vietnam. Did they support it or oppose it? Did they protest or remain passive? Did they honor those who served or scorn them?

At a time when many students were questioning why their colleges or universities were so closely connected to the government and whether or not they should have ROTC programs, McCuddin and many like him – outstanding students and fine young men – chose schools that were the ultimate ROTC programs.

It’s easy to say that those who enlisted in the military or were drafted and sent to Southeast Asia as grunts had few other choices, but the kids who went to the military academies at West Point, Annapolis or Colorado Springs were the crème de la crème, and some of them chose the academies over Harvard, Yale or other top schools.

At a time when students at other schools were questioning everything from patriotism to motherhood, McCuddin and others like him were living the mantra of duty, honor and country.

For all those who disagree, there is still no denying that our country is still around after more than 230 years because of the men and women who shed their blood. Not all of them were “gung ho” patriots or flag wavers, but they answered the call when it came.

Even at the height of protests over the war, we knew that. The rock group Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, no fans of the war, still did a song that summed it all up.

“Find the cost of freedom … buried in the ground.”

Still, if the baby boom generation was going to be the one to rebel, it hadn’t really started in 1967, especially in the South and in military families. Mike McCuddin might have had friends who questioned whether he should go into the military, but even at 17 he was still very much the boy who had played with model airplanes and admired the men who flew the real ones.

“When I was at Annapolis, I was trying to conform and survive there, even to excel,” he said. “Yet at the same time I was questioning the very foundation of the system I was trying so hard to be a part of. The reality I was discovering wasn’t matching the idealistic picture that I had walked in with.”

His parents had World War II, with its easily defined heroes and villains and goals that needed to be achieved. We had Vietnam, a war whose value to the U.S. and its citizens was based on theories that have since been called into question.

Was the Domino Theory valid?

Would the U.S. ever have been in danger if the Communists won in Southeast Asia?

Was it worth 58,000 American lives?

“A few years later, I was beginning to think my friends were right,” McCuddin said. “The Naval Academy and the Navy were not exactly right for me. I had too many questions about what we were doing and why we were doing it. Sometimes we were doing all the right things for all the right reasons, and sometimes we weren’t. Sacrifice, pride, and camaraderie battled greed, fear, and self-righteousness on a daily basis.

“This balancing act played itself out at every level, from our nation’s highest leaders to the lowest levels where our sailors and marines were just trying to do their jobs and get ahead. Where did I fit in this enormous and complex organization that I didn’t always agree with? What could I do that would be enjoyable and rewarding, and make a difference?”

In the end, he stayed in 20 years and did the best he could.

“I just tried to find and stay in that niche that was right for me,” he said. “To be a positive part of what I had thought so highly of when I was just a kid.”

***

In the end, the words of the Harry Chapin song that supplies the title of this chapter say an awful lot about McCuddin. Yes, he has traveled the world, and more than 40 years after graduating from W.T. Woodson High School he is far less callow, far more experienced and knowing than the 17-year-old boy who spoke at graduation of the first day of the rest of our lives.

He is a man, a man who has made by most accounts a positive mark on the world. A man who has been remembered fondly by the friends he made as a boy on the other side of the country.

One of Colvocoresses’ fondest memories of his lifelong friend was of a crisis.

“Mike has a very generous nature and also an adventurous spirit,” he said. “That combination of traits came together for one my more memorable episodes of our years together in Fairfax.”

The two boys were hanging out at Colvocoresses’ house one afternoon when Jim’s youngest sister Judy, 10 at the time, came into the house crying and bleeding. She had crashed while riding her bicycle and had lost one of her two top front teeth when she hit the handlebars.

“She thought she would really be in trouble for doing this, and sheepishly showed us her tooth clutched in her hand,” Colvocoresses said. “Mike and I had learned enough medicine from television shows to be able to assure her that if we wrapped the tooth in a wet cloth and got to the dentist quickly, the tooth could be put back in and saved.”

Just one problem. Both mothers were out shopping and both fathers weren’t due home for hours.

McCuddin found a solution. He said he could drive her there in his sister Sharon’s car. Sharon was away at college and her Volkswagen bug was sitting in the driveway.

“He knew where the keys were,” Colvocoresses said. “At this point Mike had had his learner’s permit for about a week and maybe two driving lessons, but off we went. Literally every stop sign or red light along the five-mile trip turned out to be an adventure in the stick-shift Bug, with stalls outnumbering rubber-peeling jump starts about 2-1, more due to the underpowered nature of the car rather than Mike’s timidity with the gas pedal.

“Well, miracles do happen, because no one got hit or pulled over and my sister still has that tooth today.”

Bob Douthitt may not have known him that well in high school, but the two became good friends in their fifties and will probably be that way for the rest of their lives.

“To me, there has been a reassuring aspect of meeting up again with so many classmates here in the Northwest the past few years, and Mike exemplifies that feeling,” he said. “As we march through life and move to new places, meet new friends, and lose touch with most elements of our past life, I think there is sometimes a tendency to think we are evolving and changing more than we really are.

“It makes it easier to not regret the loss of a prior connection if you think it wouldn’t fit with you that well now anyway. However, I think that attitude doesn’t give either our younger or current selves enough credit. In reality, I think we just develop more new ways to connect, but don’t lose the old ones.”

Dale Morgan is another 1967 graduate who became friends with McCuddin after those years at Woodson.

“I didn’t know Mike at all in high school,” she said. “I wanted to, but I don’t think we were ever in the same class. I remember being very impressed with the fact that he got involved in our class the way he did.”

Morgan, who has done more than anyone else to keep class members in touch with each other through reunions and other activities, finally got to know McCuddin at the 20-year reunion in 1987.

“Mike and his lovely wife Wendy had just returned from Hawaii,” she said. “Ronnie Millner and I got together with them. We have exchanged Christmas cards ever since, and I feel like I have known both of them forever. At our 2008 summer reunion in the Northwest, Mike organized and taught all of us to kayak. He is a great and patient leader as I am sure he was in high school.

“I see him as strong, loyal, a take-charge guy and very reliable,” Morgan said. “He values his friendships. I think he is really an all-American kind of guy.”

It really is true that old friends mean so much more than the new friends. They see where you are today, and they know where you were – and who you were – 40 years ago.

“It really doesn’t take long to re-establish a feeling of kinship with those you knew moderately well, but also be able to enjoy people you didn’t know at all – plus any of their spouses,” Douthitt said. “Then you leave with a feeling of ‘You know, there was always a reason I liked Mike McCuddin.’”